Predestination is the belief that everything that will happen has already been decided by God or fate and cannot be changed. MICHAEL S. COLLINS tells us why it’s such a popular concept in horror.

John Betjeman, the British poet exemplar, was a polymath.

He wrote the finest satirical poetry of the 20th Century (Westminster Abbey is a favourite, as is Diary of a Church Mouse).

He campaigned against the fiendish Dr Beeching, and that we still have St Pancras Railway Station is a testament to his struggles. (Hence why there is a statue of the poet in the station!)

He was also, however, a man who believed in predestination.

What is predestination?

You see, while living with the future Diana Mosley (nee Mitford) in the 1920s at Biddesden House, Betjeman had a dream in which cloaked figures handed him a card on which was enscribed his date of death. The poet spent the rest of his life convinced this was the date he would go on, and worked accordingly. He never told anyone the date he was given, so we shall have to assume it was the 19th May 1984, otherwise he got a hell of a surprise.

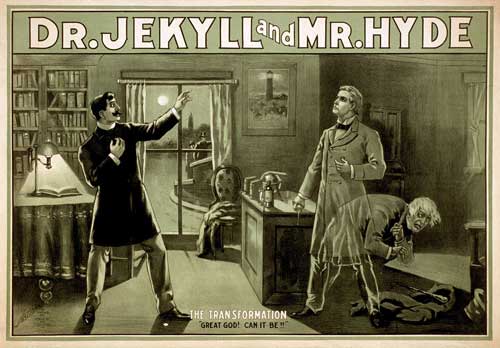

Predestination is a recurring theme in British horror, however, and one of the finest dabblers in the art was Robert Louis Stevenson. Of his Treasure Island and Kidnapped, much is known. His Bodysnatchers are becoming better known. His Jekyll and Hyde have become one of the standard textbooks of horror, adapted and performed nearly as often as Shakespeare.

But the first hints of Jekyll appeared in a short story written for Pall Mall Magazine in 1884. Markheim is a tale which doesn’t so much focus on predestination as wrestle with it. A desperate man kills a pawn shop dealer, and just as he is about to make good his escape, from the scene of his first impulsive crime, he comes face to face with a character who he takes to be the Devil.

An argument on the nature of good or evil, as Markheim fights for the essential character of his own soul against the idea that his entire path has been set without free will, forms the basis of a short but intriguing tale. In the end, Markheim shuns the shackles of predestination, finding the third way. Or does he? Readers often assume that Stevenson’s final paragraph opening suggests that the visitor is in fact an Angel and not a Devil.

“The features of the visitor began to undergo a wonderful and lovely change: they brightened and softened with a tender triumph, and, even as they brightened, faded and dislimned.”

But then, what if the great free will decision of Markheim was in fact already predestined, and what we have is a demon happy? Stevenson leaves it blank, he would explore the nature of good and evil more thoroughly through Mr Hyde and the doomed Jekyll, but in Markheim we find the whole crux of the issue, distilled into 10 pages.

Predestination is not an element solely the domain of Victorian horror. Modern horror likes to play on it, the popular and visceral Final Destination series being a case in point.

It seems that, be we a Poet Laureate, a modern horror film, or a Victorian deep in the angst of existentialism, the theories of what in life was preordained live onwards.

What it shows, at the very least, is that people love a good horror tale. And the helplessness of being unable to change course, due to outside events being mapped out for you, adds to the horror of inevitability.