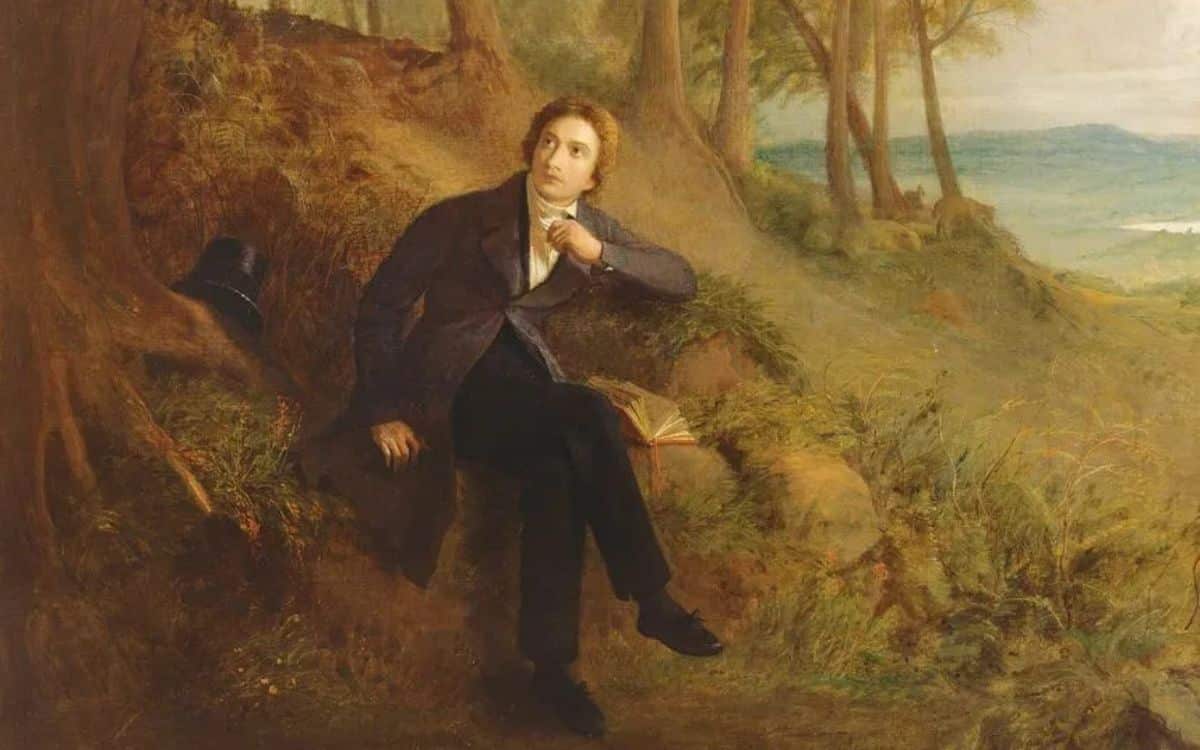

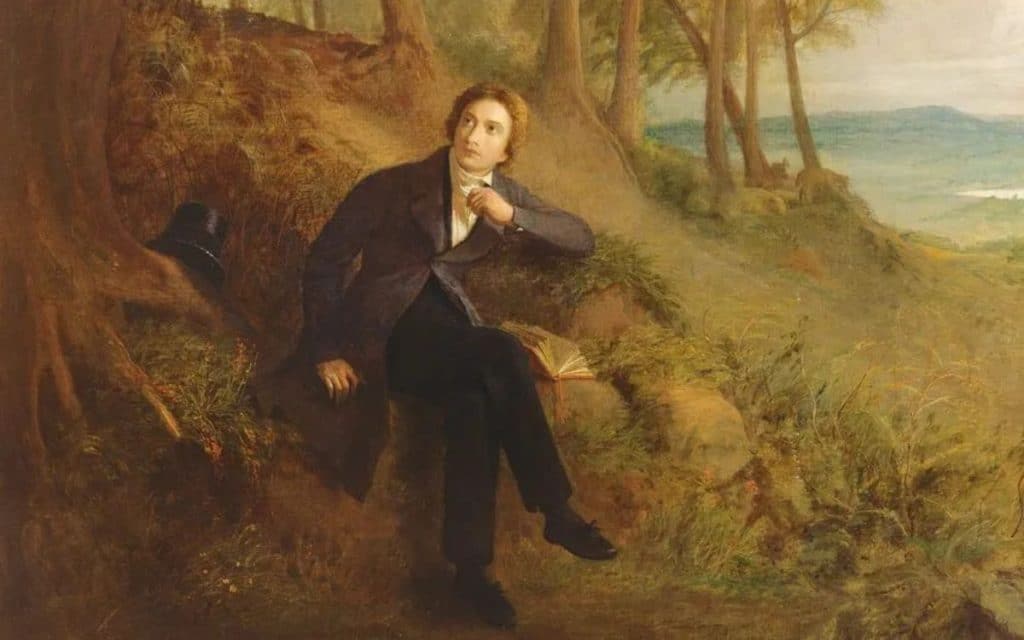

La Belle Dame Sans Merci reveals John Keats’ fascination with the tragic interplay between beauty, love and death, writes WILLIAM BOVE

This poem, by the brilliant Gothic Romantic poet John Keats, extends an invitation into a rich fantasy landscape, teeming with mythical themes.

It enchants us, filling our souls with the wonder of fairy magic, true love, and death. Do you have to be dead or dying to enjoy a world of magical wonder? Surely not — but when it comes to passion beyond reason, it can certainly help.

We open with a man — a bold knight — who, it is strongly suggested through playful wit and romantic motifs, is dying. He is found withered by sickness, time, and experience. “What can ail thee, wretched wight, alone and palely loitering? The sedge is wither’d from the lake, and no birds sing.”

The soul of life has drained from the knight; he resembles a ghost, a fading form. The natural world around him reflects this decay — the plants by the lake are withered, and the air is silent. Then, the speaker probes further: “So haggard and woe-begone? The squirrel’s granary is full, and the harvest’s done.” Autumn ends, and winter approaches — a winter that will claim the knight. He is already ailed by his limitations, slowly consumed by death. Nature, with a knowing smile, mocks his mortality.

“I see a lily on thy brow, with anguish moist and fever dew; and on thy cheek a fading rose fast withereth too.” Lilies, symbols of death, highlight life’s fragility. A lily rests on his brow — a sign that death draws near. The fever grips him, and life clings by a thread. The rose of vitality fades from his cheek, its colours draining swiftly. Death is not just coming — it races toward him.

Then, he meets a woman of mythic soul. Her beauty is so rare and strange that she can only be a faery’s child: “Her hair was long, her foot was light, and her eyes were wild.” Her untamed hair, silent steps, and wild eyes cast a spell. One cannot help but look at her, become lost in her, and surrender one’s soul. She is unearthly — a vision of magic and seduction.

He sets her upon a “pacing steed,” walking with her at a gentle pace to savour every moment. His time is now entirely hers. In lifting her to the steed, he places her needs above his own. She is elevated — her beauty transcending nature itself.

It’s a humble, gentlemanly gesture — the hallmark of a true knight. She leans sideways and sings a faery’s song, her enchantment now focused entirely on him. Her serenade is a spell of love, filling his heart with wild, intoxicating magic.

He weaves a garland for her head, bracelets too, and a “fragrant zone.” These are not just tokens — they’re vows of love, symbols of devotion, gestures of sacred union. “She look’d at me as she did love, and made sweet moan.” With a lover’s gaze and a moan of deep contentment, she returns his affection. “For sidelong would she bend and sing a faery’s song.” Her attention does not waver; her song deepens the spell, an expression of her truest self.

“She found me roots of relish sweet, and honey wild, and manna dew, and sure in language strange she said, ‘I love thee true.’” She forages a wild potion — roots and honey and dew — and in a strange tongue, professes true love.

“She took me to her elfin grot, and there she wept and sigh’d full sore; and there I shut her wild wild eyes with kisses four.” But a mortal, even a noble knight, cannot survive the kiss of a faery. Her spirit is too fierce, her passion too great. With each kiss, a piece of him dies — until at last, he is no more.

Fun fact: The Gothic Romantic period, of which John Keats was a vital figure, sought to revive imagination, beauty, and art. Keats wrote La Belle Dame Sans Merci for his brother, who had died of tuberculosis.

Tell us your thoughts on La Belle Dame Sans Merci by John Keats in the comments section below!