Shades of Frankenstein and Quatermass meet in Stephen Gallagher’s Chimera. RICHARD PHILLIPS-JONES looks back on director Lawrence Gordon Clark’s return to the genre with ITV’s 1991 adaptation.

BROADCAST: 7-28 July 1991 (in four parts)

STARRING: John Lynch (Peter Carson), Christine Kavanagh (Alison Wells), Kenneth Cranham (Hennessey), Peter Armitage (Sgt. Crichton), Emer Gillespie (Nurse Tracy Pickford), Sarah Winman (Julia), George Costigan (Schaffer), Pip Torrens (Windeler), David Calder (Dr. Jenner), Douglas Mann (Chad)

WRITER: Stephen Gallagher (from his own novel)

DIRECTOR: Lawrence Gordon Clark

Chimera 1991 Review

Nurse Tracy Pickford has barely started her new role at a rural fertility clinic in Cumbria, The Jenner Institute when she becomes suspicious of activities taking place in an annex to the main building. It becomes apparent that the fertility services are simply a public front for something more clandestine, involving animal research and genetic engineering.

When snooping around a mud-strewn van on the premises, Tracy finds a finger-written message in the grime, reading “HELP ME”. A disturbed Tracey leaves a telephone message for her ex-boyfriend, film critic Peter Carson (Lynch), asking him to call her as soon as possible.

On hearing the message, and sensing something is wrong, Peter drives up from London immediately but, by the time he arrives, most of the staff (Tracy included) are dead, slain brutally, and a great deal of the premises have been burnt out in a violent blaze.

The police seem cagey about details, the locals are in the dark and a mysterious official named Hennessey (a suitably oily Kenneth Cranham) seems to be doing everything he can to keep a lid on things.

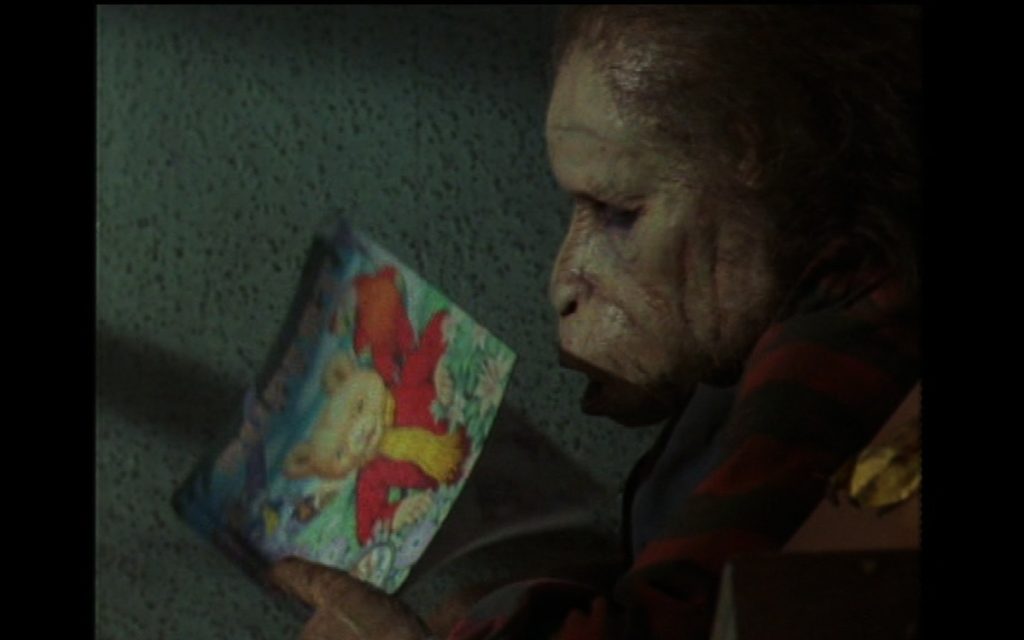

Meanwhile, on a nearby farm, two children have taken in a lonely individual in a red plaid shirt who they refer to as “The Scarecrow”. This is actually Chad, a result of the experiments taking place at the clinic, but was he released deliberately? And just why did Dr. Jenner’s assistant, Alison Wells choose that particular night to leave for London?

Chimera marked the genre return for one of Spooky Isles’ favourite directors, Lawrence Gordon Clark after a 12 year absence (see footnote) and he clearly had no trouble getting back into his groove, taking Stephen Gallagher’s narrative from Quatermass-evoking chills in the first couple of episodes (the premier episode stands up as a cracking little horror movie in its own right) to the final instalments which climaxed with scenes which couldn’t help but jog memories of Karloff’s persecuted creature in Frankenstein (1931).

In balancing these two very different aspects to the narrative, Chimera doesn’t reveal Chad to the audience until the third episode and, assisted by fantastic prosthetics and animatronics (see footnote), Douglas Mann does a sterling job in the role, winning sympathy for the pitiable child-creature whilst never letting it be forgotten that a violent outburst could come at any second. It’s a juxtaposition which is perfectly captured in a moment when Chad snarls towards the camera whilst holding a Rupert the Bear annual.

Viewed today, Chimera feels very much a product of its moment, tapping into a very specific early 90s unease about science, industry and institutional secrecy. Britain was still shaking off the Cold War, tabloids were running weekly scare stories about cloning and genetic manipulation, and ITV — not yet neutered by the homogenisation that would soon come from deregulation and the loss of regional franchises and identities — was still willing to commission material with a genuinely abrasive edge. That combination of cultural anxiety and creative freedom gives Chimera its distinctive flavour: part conspiracy thriller, part industrial horror, part cautionary tale about what happens when scientific ambition outpaces moral responsibility.

All these years later, Chimera remains an oddly neglected entry in British genre television, although its treatment by the channel that screened it can’t have helped (see footnote). It’s ambitious, atmospheric, and far more emotionally nuanced than its “genetic experiment gone wrong” premise suggests. What begins as a clinical conspiracy thriller slowly mutates into something closer to gothic tragedy, anchored by Lawrence Gordon Clark’s steady hand. That Chimera is still so fondly remembered by those who caught its original broadcast speaks volumes.

TRIVIA POINTS: Some interesting casting of smaller roles in Chimera included Paul O’Grady as a sign language interpreter, Liza Tarbuck as a coach passenger helping Carson avoid the police and David Neilsen (later Coronation Street’s Roy Cropper) getting on the wrong end of Chad’s temper.

More on those make up effects: Chimera benefitted from the expert team at Image Animation whose craftspeople had previously worked on the first two Hellraiser films (Kenneth Cranham also appeared in the second), Lair Of The White Worm, I Bought A Vampire Motorcycle and Nightbreed.

FOOTNOTES: It might have been twelve years since his previous genre effort, Casting The Runes (1979) but Lawrence Gordon Clark had been far from idle. A very busy 1980’s saw him helming the controversial Harry’s Game (1982) for the newly founded Channel 4, and a superb adaptation of Jamaica Inn for HTV (1983, with a truly chilling performance from Patrick MacGoohan) and he would return to creepy territory as producer and (on two episodes) director of Chiller in 1995.

Despite what was (as far as I can recall) a warm reception from audiences at the time, Chimera wasn’t treated terribly well after its initial broadcast. A recut version aired on ITV as a two hour TV-movie in August 1994, reducing the opening episode to a fifteen minute teaser and losing much of the story’s character exploration and plot explanation along the way (this may have been the version that appeared in the US on video, under the crass title of Monkey Boy).

Thankfully, Revelation Films released the original 4-parter to DVD in 2010, supplemented with some personal on-set footage from Stephen Gallagher, who also provided fascinating narration for it. It provides a rare and welcome chance to actually watch Lawrence Gordon Clark at work.