St Mary’s at Lambeth reveals a hidden world of occultists, curiosities and bizarre legends, writes DAVID TURNBULL

On 1 June 1967, the same day the Beatles released Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, Brixton-born David Bowie released his debut solo album David Bowie.

The final track on side two, Please Mister Gravedigger, is a rather creepy and unsettling piece. Half spoken, half sung in the Anthony Newley style Bowie was experimenting with, the song describes a child murderer watching a gravedigger uncover a locket belonging to one of his victims. He threatens the man into silence.

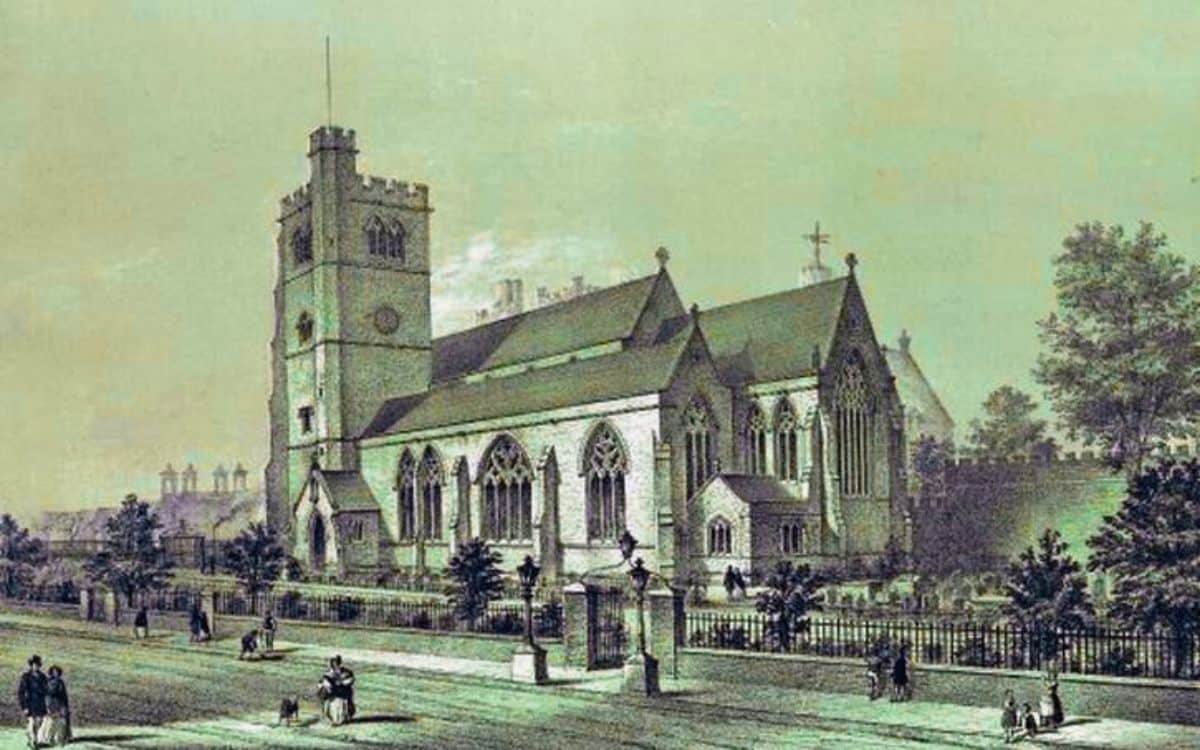

It mentions a “little church along the way which used to be Lambeth’s finest array”, bombed during the Blitz in the Second World War. St Mary’s Church, on Lambeth Palace Road, fits the description, having suffered heavy bomb damage and the loss of its stained-glass windows.

Deconsecrated in 1973, the church and its yard are now home to the Garden Museum. Before that transformation, its atmospheric interior was used in Richard Donner’s The Omen (1976) to depict the Italian monastery where Gregory Peck’s character uncovers the Satanic origins of his son, Damien.

The first wooden church on the site was built in 1062 by Goda, sister of Edward the Confessor. Later replaced by a stone structure, its proximity to Lambeth Palace made it the final resting place of several Archbishops of Canterbury.

Captain (later Admiral) Bligh, of Mutiny on the Bounty fame, is also buried there. His tomb celebrates his role in introducing breadfruit to the West Indies but omits that he was hired to feed enslaved people and that his crew famously mutinied against him.

Another notable burial is Jeanne de Valois-Saint-Rémy, a French aristocrat linked to the infamous Affair of the Diamond Necklace, a scandal contributing to the downfall of Marie Antoinette and the French monarchy.

For readers of Spooky Isles, it’s the site’s occult connections that are most compelling.

In 1611, Simon Forman, an astrologer and occultist active during the reigns of Elizabeth I and James I, was buried here. Born near Salisbury, he was apprenticed to a merchant dealing in salt and herbal medicine, which sparked his interest in healing, astronomy and the occult.

He acquired a copy of the Picatrix, a 400-page grimoire of astrology and talismanic magic, originally written in Arabic. After his apprenticeship, he moved to London to practise medicine. He claimed to have cured himself of the plague in 1592 using a secret formula and claimed to diagnose and treat illnesses by reading the stars.

This brought him into conflict with the Royal College of Surgeons.

He spent his last decade in Lambeth with his much younger wife, keeping detailed casebooks on over 2,000 clients. These notes included everything from star charts to advice on romance, correspondence, even locating lost socks.

Forman’s most chilling prediction was of his own death: he foresaw himself drowning in the Thames, and he did – his boat capsized, and he was pulled under.

Death did not close his story. He was later implicated in the poisoning of Sir Thomas Overbury. Forman was accused of creating magical means to help Frances Howard, Countess of Essex, win the affections of Robert Carr. During the trial, he was labelled an “Agent of the Devil”, a name that haunted his reputation.

Also buried at St Mary’s are the Tradescants – three generations of John Tradescants – known for their contributions to botany and collecting curiosities.

Their family tomb, near Bligh’s, bears occult symbols, including skulls and a five-headed hydra. The elder Tradescants travelled the world collecting rare plants and unusual artefacts, many with esoteric or mystical associations.

Their home, Turret House, renamed “The Ark”, became England’s first public museum – the Musaeum Tradescantianum. The building was demolished in 1881, but Tradescant Road still bears the family name.

Though the Tradescants were not occultists themselves, their collection included one of the strangest curiosities ever assembled: the Barometz, or Vegetable Lamb of Tartary.

Said to grow from the earth, tethered by a stem, this mythical creature would graze its surroundings until it died from starvation. It inspired poetic tributes, including one from Cannobia Florum (1791) by D. De La Croix:

“For in his path he sees a monstrous birth,

The Borametz arises from the earth

Upon a stalk is fixed a living brute,

A rooted plant bears quadruped for fruit…”

You can view the Barometz and its story at the Garden Museum’s website:

https://gardenmuseum.org.uk/collection/barometz-or-vegetable-lamb

Tied closely to the Tradescants and Lambeth is Elias Ashmole, founder of Oxford’s Ashmolean Museum. Born in 1617, Ashmole was a solicitor, Freemason, royalist, astrologer and avid collector.

He catalogued the Tradescant collection, moved next door to The Ark, and began acquiring his own artefacts, including Forman’s casebooks and his copy of the Picatrix. Unlike the Tradescants, Ashmole had deep ties to alchemy.

Mentored by alchemist William Backhouse, who claimed descent from Hermes Trismegistus, Ashmole was spiritually adopted and supposedly gained access to ancient esoteric knowledge.

In 1650, he published Fasciculus Chemicus, and in 1652, Theatrum Chemicum Britannicum, a major alchemical work.

Ashmole coveted the Tradescant collection and persuaded John Tradescant the Younger to bequeath it to him – allegedly while under the influence of drink. After Tradescant’s death in 1662, his widow Hester contested the agreement, but a court upheld it.

In 1678, Hester was found drowned in her garden pond. Ashmole took possession of the collection and later donated it to Oxford University in 1677. It took eight wagons to move it from Lambeth.

When Ashmole died in 1692, he too was buried at St Mary’s.

Learn more about the Ashmolean Museum: https://www.ashmolean.org

After filming The Omen, St Mary’s fell into disrepair. By 1977, the churchyard was overgrown. Rosemary and John Nichols, keen gardeners and Tradescant enthusiasts, visited the neglected site. Horrified, they founded the Tradescant Trust to preserve the church and the tomb.

They succeeded in saving both, and in 1980 the Garden Museum opened its doors.

Today, visitors can see part of the Tradescant collection on display. Entry is free, and the Tradescant tomb can be found in the courtyard beside the museum café.

Plan your visit here: https://gardenmuseum.org.uk/visit

Have you explored the Garden Museum or uncovered stories at St Mary’s at Lambeth? Share your thoughts in the comments!