Psychic visions, dreams and spiritual beliefs have played a mysterious role in some of archaeology’s most extraordinary discoveries, writes JAIMIE LEE-BARON

Archaeology, along with history, allows us to reconstruct our past and gain valuable insights into how our ancestors lived. Thanks to modern innovations such as geophysical surveying equipment and carbon dating, we now have a more accurate lens on the past than ever before.

But just sometimes, archaeologists employed far more unconventional means to help them in their discoveries. And they were no less effective.

We will take a look at a few of the most famous cases here.

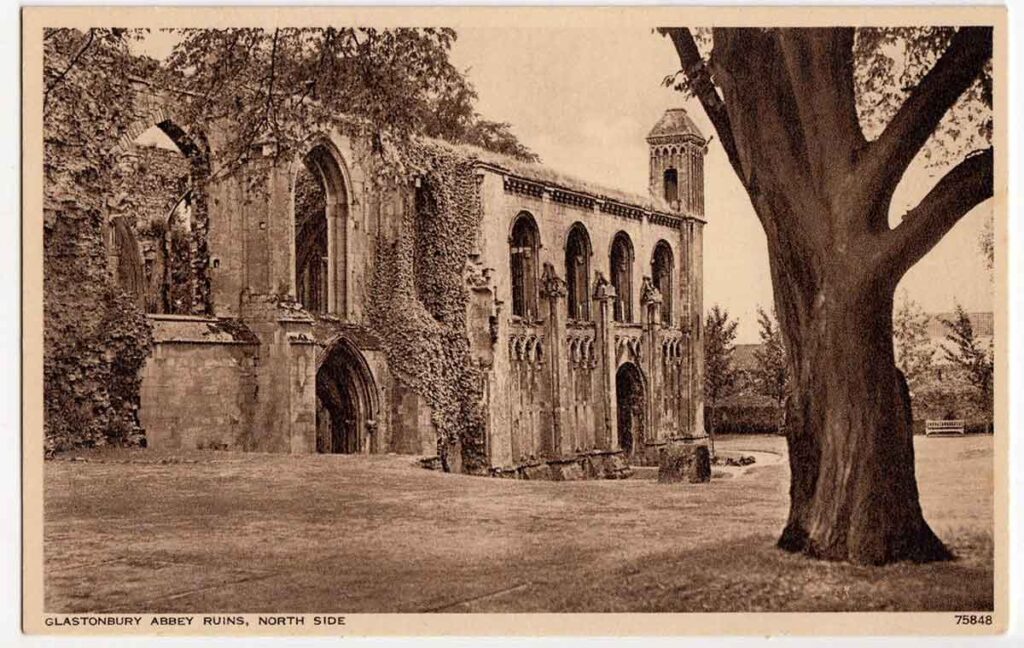

Glastonbury Abbey: Frederick Bligh Bond (1864–1945)

Frederick Bligh Bond was an architect and archaeologist specialising in church architecture. In 1908, the Church of England appointed him Director of Excavations at Glastonbury Abbey, and it was here that he began employing psychic methods to assist his work.

Glastonbury Abbey had always fascinated Frederick. He was absolutely convinced that the dimensions of the abbey buildings conformed to “Gematria” (this is rather complicated and would demand a long time to explain in any detail—for now, just think of numerology and sacred geometry) and had co-authored a paper to this effect in 1899.

Sure enough, his work proved extremely fruitful. He rediscovered a number of important buildings at the abbey, including the Edgar Chapel. In fact, his success rate at knowing where to dig and what to discover was, well, almost uncanny.

It wasn’t until years later, in 1918, that he revealed the reason for his outstanding success rate: the employment of psychic practices.

In his book The Gate of Remembrance, he documented his use of “automatic writing” to contact the spirits of deceased monks—most notably one “Brother Johannes”—who, in turn, described the dimensions of buildings he was searching for and directed him where to excavate.

He was aided in these efforts by his close friend, retired naval captain John Allen Bartlett (whom he calls “John Alleyne” in the book), who was a noted psychic at the time.

Of course, these claims did not impress the Church of England at all, and in 1921, Bishop Armitage Robinson gave Bligh his marching orders.

Now, it has to be said that Frederick was a good architect and had designed some beautiful structures prior to his Glastonbury work. However, he also had a deep interest in spiritualism, mysticism and even the occult.

He joined both the Theosophical Society and the Society for Psychical Research, and became a member of the Societas Rosicruciana in Anglia (a Rosicrucian group limited strictly to members of Freemasonry).

In 1926, he emigrated to the United States, where he was employed as the education secretary of the American Society for Psychical Research. He also became an ordained minister in the Old Catholic Church of America and, in 1933, was consecrated a bishop in the same church.

When all of this is thrown into the mix, it becomes more understandable that he might employ such practices in his work at Glastonbury. And there can be no doubt that he carried out very detailed and accurate excavations whilst there.

Visitors to Glastonbury Abbey are still benefitting from his labours to this very day.

Sutton Hoo: Edith May Pretty (1883–1942)

Sutton Hoo was the most extraordinary archaeological discovery of Anglo-Saxon artefacts ever found in England. It was the type of dig every archaeologist dreams about, yielding everything from coins, weapons and armour to a full-scale boat.

How was it located? By a woman experiencing vivid dreams and seeing apparitions.

Mrs Edith May Pretty was a confident and forceful woman, serving as a magistrate and having worked as a nurse during the First World War. She was intelligent and practical—the type you wouldn’t want to mess with.

Having inherited a fortune from her father, Edith was independently wealthy. When she married her husband, Frank Pretty (a war hero and successful drapery business owner), she bought the Sutton Hoo estate, and the couple resided in Sutton Hoo House.

The estate comprised over 500 acres, which included several mounds. Most of these had been plundered long before Edith ever owned the land, so they went largely unnoticed. That is, until something strange happened.

Sometime in 1937, both Edith and her friend Dorothy Cox began to see ghostly figures of Anglo-Saxon soldiers patrolling a particular group of the mounds.

Edith also reported having an extremely vivid dream in which a helmeted warrior on a white steed was being buried under one of the mounds with a lot of golden objects. She shared this experience with local historian Haydn Williams, who recorded the paranormal phenomena and suggested that the particular mound might be worth excavating.

Barely a year later, she contacted Basil Brown, a local self-taught archaeologist, to begin a dig on the site.

And the rest, as they say, is history. But there are certain aspects of this case that deserve mention.

Edith’s father, Robert Dempster, was a keen amateur archaeologist who had excavated historical sites near their family home, Vale Royal Abbey in Cheshire. This likely helped inspire Edith to explore the mounds on her property.

When Edith’s husband, Frank, died in 1934, she became very interested in spiritualism—no doubt hoping to contact her dear departed on the “other side”. Toward this end, she consulted mediums and became a benefactor of the local spiritualist church.

She also became close friends with W. T. Parish, the famous faith healer whose help she had enlisted in trying to save her dying husband. She financially supported Parish in his work, helping him to establish a Centre for Healing in East Sheen, London.

Parish is said to have conducted a séance for Edith at Sutton Hoo, during which a ‘black warrior on a black horse’ appeared and directed her to begin excavating the mounds. This remains pure conjecture and is not taken too seriously, but from the above we can say that:

Edith Pretty was interested in archaeology.

She was also interested in spiritualism.

When combined, these two interests might well have inspired her to explore the mounds.

Whatever the reason, the fact remains that the dig uncovered a truly magnificent hoard of artefacts and riches. And even though the state determined that all of it legally belonged to Edith, she very happily donated the entire collection to the British Museum.

She was later offered a CBE by the then Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, but declined.

To end with a suitably spooky side-note: strange phenomena are reported to this very day in the British Museum gallery that now houses these rare and precious artefacts. Everything from doors locking and unlocking themselves to visions of silent Anglo-Saxon warriors. Still watching. Still guarding.

Ancient Egypt: Dorothy Eady (1904–1981)

Our final subject is especially intriguing. It is one of the more widely accepted cases of apparent reincarnation, purely by weight of evidence—the case of Dorothy Eady.

Dorothy was born in Blackheath, London. Her father was a tailor, her mother a housewife.

At the age of three, she suffered a terrible fall down the stairs and was pronounced dead by the attending physician. However, she later regained consciousness, seemingly unharmed—except that her personality appeared to have changed.

She began to exhibit strange behaviours, repeatedly asking to be “brought home”. She also developed a “foreign accent syndrome” and began comparing what she learned at Christian Sunday school to ancient Egyptian doctrine.

This caused considerable consternation. Her parents were asked to withdraw her from further religious instruction.

Dorothy was expelled from school for refusing to sing a hymn that asked God to “curse the swart Egyptians”. When she began attending Mass at the local Catholic church, she came to the attention of the priest, who visited her parents, interrogated Dorothy himself, and forbade her from returning.

However, when her parents took her to visit the British Museum, everything started to fall into place. Dorothy ran from one Egyptian deity to another, kissing their feet and proclaiming, “These are my people!”

From that moment on, she took every opportunity to visit the museum’s famous Egyptian galleries. Eventually, she came to the attention of Egyptologist E. A. Wallis Budge, who was impressed by her passion and encouraged her to study hieroglyphics.

In the years that followed, Dorothy moved to Egypt, working alongside some of the world’s leading Egyptologists as a draughtswoman and caretaker of antiquities.

She firmly believed she was the reincarnation of a virgin priestess named Bentreshyt (Harp of Joy), who had served at the temple of Seti I in Abydos. After engaging in a forbidden affair and falling pregnant, the priestess had chosen suicide to avoid scandal.

This might have been dismissed out of hand, but while working at the Abydos dig, Dorothy amazed the archaeological team by accurately pointing out where the gardens had once been and identifying a previously unknown tunnel—the “Osirion”.

She also demonstrated the extraordinary ability to recite complex hieroglyphs inscribed on temple walls while blindfolded and in complete darkness.

In addition, she hinted that a further discovery would be made in the tomb of King Tutankhamun. And in 1998, a full 17 years after her death, archaeologists indeed found anomalies suggesting a hidden tomb behind one of the walls. Investigations are ongoing.

Dorothy eventually retired near the temple where she believed she had once served. In later life, she became a respected healer among the locals, who admired her dedication to ancient Egyptian rites.

She was also respected by many in the Egyptology community, who acknowledged the assistance she had lent to their work, even if they did not fully share her beliefs.

Though she was not permitted to be buried in the tomb she had built for herself, she was interred nearby, laid to rest close to the temple she knew so well.

The tales of the exceptional people recounted above are all a matter of record, and much more information is readily available on each of them.

Each seemed to possess some kind of supernatural ability that enabled them to find hidden things that had remained concealed for centuries—long before the advent of today’s sophisticated archaeological technology.

They are certainly interesting in terms of what they managed to accomplish. But taken together, they raise fascinating questions about how they were able to do what they undoubtedly did.

They still captivate us now.

We need to be mindful that the invisible world is around us always, and in all kinds of ways.