On this most spooky of nights, REN ZELEN looks at two classic US horror films with definite British connections – Halloween and Psycho!

John Carpenter’s movie Halloween had its premiere in the US on October 31st 1978.

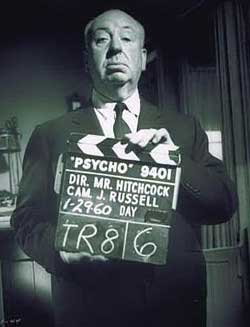

Although touched upon in smaller British cult movies such as ‘Peeping Tom’, the components and themes used by Haloween had not been used in a major feature film for some time, not since its obvious inspiration and cinematic predecessor, English director Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960).

The horror movie had been evolving away from its representation of classical monsters such as Frankenstein, the Wolfman, Dracula or ‘The Thing’ into a less supernatural or alien creature.

The feature film monster became a man (though rarely a woman). The new monster was the psychological deviant, whose twisted mental perversion leads him to stalk and kill unwitting and innocent victims.

Psycho, and later its simpler offspring Halloween, were so successful at the box-office, they inevitably engendered countless imitators and variations.

They instigated the conventions of the ‘slasher’ movie genre that we are now so familiar with, so much so that they are able to be referenced ironically in more recent movies such as Craven’s ‘Scream’ and Whedon’s ‘The Cabin in the Woods’.

The killer is usually the product of a psychosis created by a sick or traumatic family event – the victim – a beautiful, sexually attractive woman – the place is often a twisted, dark, dank perversion of ‘home’ – the attack is often perceived from the victim’s point-of-view and most interestingly perhaps, the weapon is never a gun.

The rules of the ‘slasher’ movie require the weapon of choice to be pre-technological – the ice-pick, the axe, the razor, the machete, the chainsaw, and of course – the phallic knife – all the better to get up close and personal to a victim.

Violent physical contact is essential for the psycho monster – a perversion and sublimation of repressed penetrative sexual contact.

Undoubtedly one of the elements that made Hitchcock’s Psycho a runaway success, was his sexualisation of motive and action. The prototype of the victim is the woman, most clearly, the sexualized woman.

This is not an idea invented by the cinema, it was Edgar Allan Poe’s contention that “the death of a beautiful woman is the most poetical topic in the world”.

As for the murder or mutilation of a beautiful woman, slasher director Dario Argento puts it succinctly, ”I like women, especially beautiful ones. If they have a good face and figure, I would much prefer to watch them being murdered than an ugly girl or a man.”

Not as subtle, smart or multi-layered as Hitchcock’s Psycho, John Carpenter took similar elements and with Halloween, distilled them into a less contentious, less complex, yet perfectly executed (if you’ll pardon the pun) cinematic vehicle for a series of scary shocks and jump-in-your-seat moments.

Not to belittle Carpenter’s sophistication as a film-maker. He creates an eerie, claustrophobic atmosphere, not least by the use of his trademark soundtrack, and sets a relentless pace leaving the audience little time for consideration of any internal logic.

The initial murder that opens the film happens on Halloween night and takes place entirely from the viewpoint of the killer. It involves a lissom teenage girl being mercilessly stabbed to death with a kitchen knife, following a sexual interlude with her boyfriend in her parents’ bed. The twist comes when the murderer is revealed to be her six-year-old brother, Michael.

The film then shifts to Halloween night 15 years later, when Michael escapes from the asylum where he has spent the intervening years and heads for Haddonfield , keen to kill a few more slutty teen girls, presumably still silently enraged at the sexual wantonness of his unfortunate sister.

The role of Dr. Loomis, Michael’s doctor in the asylum, was memorably played by British actor Donald Pleasence (although the role had been rejected by fellow Brits and horror veterans, Peter Cushing and Christopher Lee).

Loomis portentously offers an insight into Michael’s psychosis, explaining that although his body may have achieved maturity, his mind remains frozen in an infantile jealous fury.

While Hitchcock allowed Psycho’s Norman Bates to display a side that was visible and to all appearances, seemed normal, Carpenter does not give the same attributes to Michael Myers.

He is emphatically an outsider, locked away from society. He moves robotically and is seen only in a mask, so he seems less than human. We catch sight of him only in glimpses, his white-rubber face emerging from the shadows of the background or the darkness of a doorway. In one aspect he seems supernatural – he survives assault after assault with superhuman indestructability. He becomes the embodiment of the kid’s mythological ‘boogeyman’.

The slutty, sexy girls and their inconvenient boyfriends are dispatched methodically, until only one girl is left. The surviving girl is the one who discovers the butchered bodies of her friends. She is then pursued, cornered, wounded – she screams, she runs – she alone is left to perceive the full horror and peril of her predicament, and we must face it with her. She is the innocent, the intelligent, the bookworm, the swot, and usually, the virgin, but it she that must finally look death in the face.

That is why Jamie Lee Curtis in Halloween fares rather better than her mother Janet Leigh does in Psycho.

As Laurie, the last girl standing, she is presented from the outset as the most sympathetic character – on the verge of dating, but unlike her companions, still unsure and shy. Protective of the children in her charge while she is babysitting, she draws on resourcefulness and courage when faced with the relentless killing machine that is Michael Myers. Just long enough to survive until she’s rescued!

Janet Leigh’s character, Marion, is revealed from the outset as a tainted woman. She is having an illicit affair and has absconded with a large sum of money. Lest we lose sympathy for her, Hitchcock ensures that we realise that she is having second thoughts about her actions and may be on the point of turning back when the tragedy strikes. The shower scene in Psycho is probably one of the most praised, studied and iconic scenes in cinema history, but there is only the most fleeting of moments when we can actually perceive the body of Marion being stabbed.

The rest is rendered in oblique images of the knife, the body and finally the bloody water as it swirls down the drain. Alfred Hitchcock’s cinematically stylish version of ‘slasher-style’ murder was probably the last to require the use of our own imaginations.

The improvements in special effects and computer generated images have made it possible to create maiming and dismemberment in the most realistic detail. With this explicitness the ‘slasher’ movie moved onto ‘torture porn’ and the all out ‘gore fest’, and with it came an inevitable desensitization. These kinds of movies have changed in tone. We can’t get any more horrific, and so beyond out and out horror there is only the ironic reference or the blackly humourous.

Happy Halloween.

Copyright R.H. Zelen – ©RenZelen 2012 All rights reserved.

REN ZELEN describes herself as “a writer, academic editor, reviewer, pop culture junkie, movie buff, rock music enthusiast, science nerd and Sandra Bullock lookalike”. Her fiction can be found on Kindle and her own website. Click here to purchase her post-apocalyptic science-fiction novel ‘The HATHOR DIARIES’. Her book/film/TV reviews can be found on various sites on the web. Information and contact on twitter @RenZelen

Comments are closed.