Witcht trials swept Scotland in the 17th century and the tiny village of Inverkip was not immune, says CHRISTINE MILLER

Inverkip is a small, unassuming village in the heart of Inverclyde, and within the historic county of Renfrewshire. Appearances are deceptive, however, as from 1640 to 1690, the village was a hotbed for a large number of witchcraft accusations, almost all of those targeted were women.

The societal climate of the day was domineeringly patriarchal, and thus it is of little surprise to discover that the vast majority of witchcraft charges in Scotland under The Witchcraft Act of 1563 were given to women. These women usually came from a particular set of demographics – they were elderly, spinsters, midwives or widows with no male spousal protection and very little money, and therefore were society’s most vulnerable.

It is important to note that Scotland had not always been fearful of witches; the country had a sizeable population of herbalists, who were known as witches, but these people (again, usually women) were not feared amongst their communities, quite the opposite in fact, they were healers who sought to help their neighbours.

By the 17th century, however, Scotland was a deeply paranoid place. King James VI (later to be James I of England) had published his infamous Daemonologie in the latter part of the previous century, yet the hangover from this was still evident many years later. The message from the King was clear – witches wish us ill and must be flushed out at all costs.

The two ministers of Inverkip were the Reverend John Hamilton and the Reverend Alexander Leslie; both of whom were known to be ‘zealot persecutors of witches’ and both actively fuelled the dreadful paranoid fire which was to envelope the area.

The victims of the Inverkip witch trials

One 1963 article from a local Scottish newspaper explains how the victims of the witch hunt would be sought out – “the normal procedure was for a search to be made for the ‘Devil’s mark’ on the suspect’s body. Even if one was not immediately visible the inquisitors did not worry too much, they convinced themselves that the absence of such a mark was merely an oversight on the part of Satan. The next tests were often a combination of plunging pins into the ‘witch’s flesh’ and tying her fingers to her toes, throwing her into a pool of water and watching the results. Needless to say the poor maltreated creature had little chance of survival either way. If she bled or screamed in agony when the pins were thrust in she was reluctantly considered innocent although by the time this conclusion had been reached she was frequently so ill and weak from shock and humiliation that the verdict meant very little. Likewise if she drowned during the water test the blessing of God was called on her soul and her worthy neighbours went off to hunt for someone else”.

Accusations Beyond Control

One of the few men who was believed to be a witch was a local landowner named Alexander Dunrod. He was rumoured to be involved with a number of witches in and around Inverkip, and even had the Devil himself come to stay with him. The following poem verse sums up the local feeling to Auld Dunrod:

“In Auld Kirk the witches ride thick

And in Dunrod they dwell;

But the greatest loon amang them a’

Is Auld Dunrod himsel’.”

Legend has it, Dunrod fell penniless, and as a result became enamoured with the black arts in the hope of restoring his fortunes. He is supposed to have died in mysterious circumstances in the grounds of one of his tenants. Witch or no witch, it appears Auld Dunrod was a very unpopular man. Still, he did not stand trial for the rumours which surrounded him, in all likelihood because he was male.

Mary Lamont

Young Mary Lamont was perhaps the most famous of the Inverkip ‘witches’. She was accused of dancing, drinking wine and eating bread with the Devil himself, as well as throwing cursed sand and transfiguring into a cat. Mary did not stand a chance against the legal system which was determined to see her convicted of witchcraft.

The trial lasted just one day, and saw Mary implicating others and confessing to all charges put against her. Although it is impossible to truly know whether Mary and those she further accused really were witches, one would tend to assume that the societal pressure spelled her confession and tragic demise.

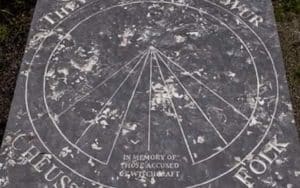

All in all, 12 people in and around Inverkip were accused of witchcraft, with only one being found not guilty. Aged just 18, Mary lost her life, and was burned at the stake for her supposed crimes. The fate of the other 11, is unknown.