What if Dracula isn’t just a horror story, but a hidden plea for compassion, told through the tragic character of Renfield and inspired by Bram Stoker’s own family?

When people talk about Bram Stoker’s Dracula, the spotlight inevitably falls on the Count himself.

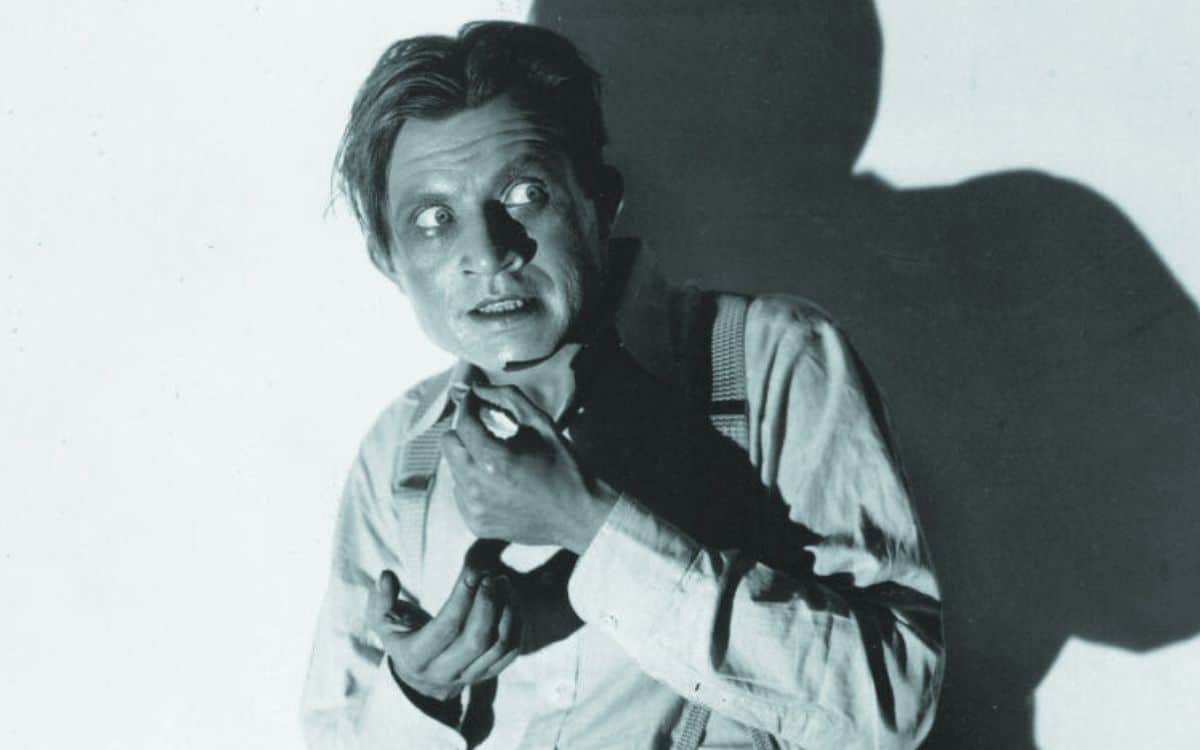

Yet one of the novel’s most unsettling figures is not a vampire at all, but a man confined in an asylum.

Renfield, with his unnerving obsession for devouring flies, spiders and birds, is one of the strangest characters in gothic literature.

To modern eyes, he appears as a grotesque Victorian cliché of madness.

But according to Stoker’s great-grandnephew, Dacre Stoker, Renfield was carefully crafted to be something very different.

“Renfield requires pity and that’s a good moral standard,” Dacre explained. “That’s what the Stokers are saying — we need to pity these people. If you pity them and treat them properly, what do you get? You get information about Dracula back to you. Renfield was even trying to look out for Mina.”

This interpretation casts Renfield not as comic relief or a sideshow lunatic, but as the product of a family deeply engaged with questions of mental health at a time when most of society dismissed such concerns.

Bram’s compassion, his sense that the mentally ill deserved dignity, flowed directly from his family background.

Who was Charlotte Stoker?

His mother, Charlotte Stoker, was outspoken in public life. In mid-19th century Dublin, she delivered papers to the Statistical and Social Inquiry Society of Ireland on subjects many women of her time would never have dared touch.

She argued for better education for the deaf and mute. She demanded reforms in working conditions for young women. Crucially, she spoke on how society should judge whether someone was criminally insane.

She believed that people with mental health problems needed to be understood, not simply locked away.

Dacre describes her as an activist who felt compelled to challenge the status quo. “She was one of those people who wanted to set the record straight and do things properly,” he said. “She gave lectures to this very prestigious society and told them they had to do better.”

It is no coincidence that her son went on to create a character like Renfield, who is treated by the “band of heroes” with medical care and compassion, rather than ridicule.

Doctor brother influences Dracula

Bram’s elder brother, Sir William Thornley Stoker, also played a crucial role. A respected Dublin surgeon, Thornley served in hospitals for mental health patients and became an inspector of vivisection, at a time when debates about the ethics of animal experimentation were fierce.

His medical fingerprints are all over Dracula. The novel’s detailed description of brain trephination surgery — performed on Renfield after his skull is fractured by the Count — was taken almost word for word from Thornley’s own notes.

He also advised Bram on blood transfusion techniques, which were ground-breaking at the time and used in the desperate attempts to save Lucy Westenra.

Bram himself went further still. He interviewed inmates at Millbank Prison in London, studying the behaviour and speech of prisoners with mental health issues so that he could capture their voices authentically.

This research explains why Renfield’s dialogue swings so eerily between lucidity, obsession and desperate appeals for help.

The combined influence of his activist mother, his medically expert brother and his own determination to research directly produced a character who was startlingly different from the usual “madman” of Victorian fiction.

Renfield is grotesque, certainly, but he is not without humanity.

He is treated with a measure of respect, his suffering is taken seriously, and in the end he performs an act of near heroism, warning the others about Mina.

For Dacre Stoker, this is no accident. “Bram’s mother’s influence and Thornley’s medical experience—that’s why Bram had Renfield in the story,” he said. “The Stokers had this desire to treat people with mental health problems better.”

Seen this way, Dracula is not just a tale of blood and horror. It also carries a hidden message about compassion.

At a time when asylums were notorious for cruelty and neglect, Stoker wrote a patient who demanded pity and care. Renfield’s tragic death underscores the seriousness with which Bram treated his plight.

It also places Stoker in the middle of wider Victorian debates.

Campaigns against vivisection portrayed scientists as cold and cruel experimenters—imagery that Stoker channels in his depiction of Dracula as an “evil scientist” conducting callous experiments on Renfield.

At the same time, new thinking about criminal insanity and asylum reform was circulating in medical and political circles — ideas Bram’s mother was directly engaged with.

Against this backdrop, Dracula reads not only as gothic entertainment but as a novel quietly grappling with the moral duty to treat the vulnerable with compassion.

Behind the blood and shadows lies a strikingly modern message: our humanity is measured not by how we fight monsters, but by how we care for those society would rather forget.

What did you think of this article about Bram Stoker and Renfield’s role in Dracula? Share your thoughts in the comments below.

Dacre Stoker is leading a trip to Romania this Halloween 2025. On our recent podcast, Dacre speaks to Spooky Isles about the adventure, as well as other thoughts on Dracula and his great-granduncle’s legacy.

- Book your Dracula adventure with Dacre Stoker: Mysterious Adventures Tours

- Listen to the full interview here: Spooky Isles Podcast with Dacre Stoker