Over recent years, western death and funerary customs have become rather homogenised, the necessities being handed over to a company, outside of the family’s confines. However, centuries ago, the people of Scotland enjoyed rather more interesting traditions.

KATE CHERRELL takes a look at these unusual Scottish death customs

The Winding Sheet

Death and Marriage. They go together like a shroud and corpse? Death was a looming presence in the life of young women, especially when they entered marriage. Indeed, many women would spin her own ‘winding sheet’ or shroud as they were making their wedding dressed.

With childbirth being a very real threat to a young woman’s life, it was a common reality that a woman would lose her life during the birth of a child.

The shroud was removed and aired every year, then placed back in their chest, surrounded by perfumed clothes and flowers.

If a young woman was to die without a shroud, she would join the realms of the restless dead, never entering heaven and bringing disease and further misfortune to her community.

Funeral Auction

Feasting at a wake is still a common practise, with the family of the deceased laying on a spread for mourners.

However, if a family was unable to afford the enormous cost of food and drink, an auction was held after the funeral, selling the deceased’s possessions to the highest bidder.

The profits from the sale would then cover the costs of the funeral and feast.

Traditionally, during this feasting, the men would dine separately from women, with the men having the more raucous time of things!

Confusing the Dead

The Victorians were rather creative when removing a body from a household.

For example, it was commonplace for a corpse to be carried through the door head-first, so that the spirit of the deceased couldn’t call any other souls to follow him.

However, the Scottish were rather more invested in their masonry.

Throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, many families eschewed the door, choosing to pass their deceased loved ones through a hatch or window.

This was thought to confuse the spirit, leaving them unable to return as a wondering soul.

Windows were too simple for some, with many Scots choosing to smash a hole in the wall of their house, passing the body through, then bricking it back up.

The Sitting or Lykewake

Following a death, a vigil was held over the deceased for several days.

In the decomposition process, the gasses in a body can escape through an orifice in a delightful belch of rotten air.

The body may twitch or move through this process, giving many relatives a false impression of life.

Watching over the body would ensure that the dead really was… dead.

Being present during daylight hours was called ‘Sitting’ and was a ‘Lykewake’ after dark.

This process was not a simple affair as, after repeated washing, games, dancing, drinking and partying would occur.

Family members would bring food, drink and tobacco to the sitters, leaving many guests unimaginably drunk and prone to gambling.

In one account referenced in Caillachs Herbarium, during a drunken game of hide and seek, “young men took the body out of the coffin and one of them hid in its place. When he was finally found he was quite dead and the body originally there couldn’t be found”.

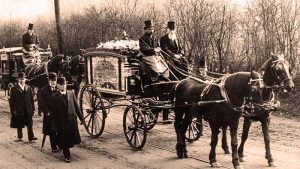

The Bell Man

In the 17th Century, a Bell Man would be a familiar presence around Scotland.

After a death, the Bell Man would wander the streets or stand in the square, ringing his bell and proclaiming that a death had occurred.

He would then dispense details of the funeral and feast, inviting people in the locality to attend.

Directly before a funeral, the Bell Man would often lead the procession, tinkling his bell and being followed by the clergy and congregation.

At this point, nothing was said – the ringing of the bell was the sole sound to accompany the dead to the churchyard.