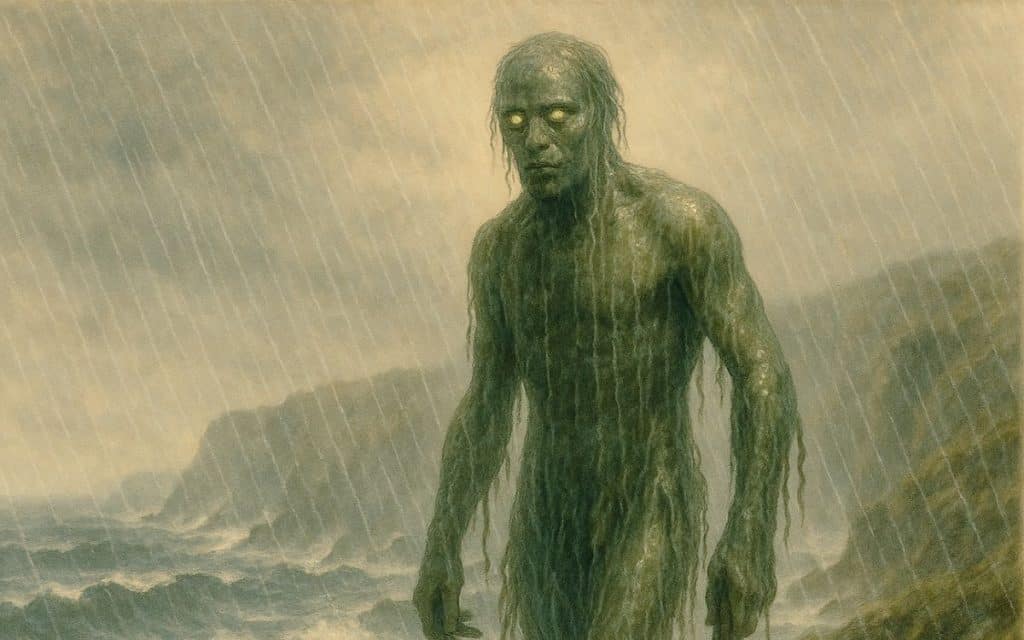

Bucca, Cornwall’s storm-bringing sea spirit, once ruled the waves with fury — and his legend still haunts the coast today

In the folklore of Cornwall, Bucca is the name given to a male sea spirit—part man, part elemental force—once believed to haunt coastal communities and tin mines alike.

He was feared and sometimes honoured, said to control storms, spoil catches, and stalk the shoreline when tempests rose.

Though belief in Bucca has faded, traces of his legend remain in place names, customs, and uneasy stories still told in Cornwall’s far west.

History of Bucca’s Name and Origins

The term Bucca has long puzzled folklorists.

First recorded in the Cornish language in the early 1600s, it referred to a spirit or goblin associated with the sea and mines.

The name may share roots with the Irish Púka and the Welsh Pwca — shapeshifting beings from Celtic folklore known for their mischief and unpredictability.

Others trace the word to Old English or even a Slavonic root for “spirit”.

By the 19th century, writers like Rev. W. S. Lach-Szyrma and William Bottrell began to suggest that Bucca could be a folk memory of a pre-Christian sea god, perhaps linked to ancient British deities like Nodens, a god of the sea and healing, or the Irish Nechtan.

These connections are speculative, but not unreasonable.

In a place where weather could decide life or death, it makes sense that early people might turn to the sea with offerings and prayers.

In Cornwall, especially around Newlyn, Mousehole, and Lamorna, Bucca was seen as more than a myth.

Up until the 1800s, fishermen were known to leave part of their catch on the beach “for Bucca” — a ritual not unlike the offerings once made to the Knockers, subterranean spirits of the mines.

These weren’t tales for children.

They were part of everyday life.

Hauntings and Legends of Bucca

Bucca wasn’t a ghost in the traditional sense.

He didn’t belong to a single human soul, but rather embodied the power and unpredictability of the sea itself.

His presence was most often felt during storms.

In fact, south-west gales were sometimes called “Bucca’s breath” or “Bucca calling”, as if the spirit was voicing his anger through the wind.

In the village of Newlyn, Bucca was considered so present that locals were mockingly referred to as “Newlyn Buckas” by those in nearby Penzance.

The nickname stuck because the fear of Bucca was real.

Fishermen would sometimes claim to hear an eerie voice in the wind, or glimpse a shadow wading through the surf during violent weather.

There are two forms of Bucca in older accounts: Bucca Gwidden, the white or “good” Bucca, and Bucca Dhu, the black or “evil” one.

This distinction suggests that the spirit could either bless or punish, depending on the mood—or the tribute offered.

One tale describes a Sea Bucca who was once a prince, cursed by a witch and condemned to live in the sea.

Though tragic, this version of Bucca still retained human traits — he loved children and helped honest fishermen, but only when respected.

When insulted or ignored, he retaliated harshly.

Unlike other ghost stories, Bucca sightings are less about visual encounters and more about presence — unseen footsteps on a cove path, pressure in the air before a storm, fish inexplicably vanishing from nets.

These moments were often quietly attributed to Bucca.

Visiting Bucca’s Coast Today

Though belief in Bucca has mostly vanished from daily life, his legend still lingers in Cornwall’s landscape — especially in the far west, where the coastline remains largely unchanged.

Newlyn and Mousehole, once strongholds of Bucca lore, are ideal places to start.

Look beyond the tourist trappings and explore the beaches and narrow lanes where fishermen once spoke of the sea spirit as if he were just another villager.

Head west to Lamorna Cove, a remote inlet with sea-carved caves and paths that twist through wind-cut gorse.

It’s here, more than anywhere else, that people have reported hearing strange sounds during storms—animal-like howls mixed with human anguish, attributed by some to Bucca Dhu.

There are no Bucca-themed plaques or museums.

The stories survive in local memory, old books, and a lingering sense of unease when the sky turns.

If you walk the coast during a gale, especially out of season, you may begin to understand why offerings were once made.

Modern pagan groups such as the Ros An Bucca coven have reimagined him as a protective sea spirit, integrating him into contemporary ritual practice.

In places as far-flung as New Zealand, new branches of “Bucca Witchcraft” now call on him in a different context.

But here in Cornwall, his name still belongs to the wind and the sea.

Have you experienced Cornwall’s wild coast and its myths? Share your stories or thoughts on Bucca in the comments below.