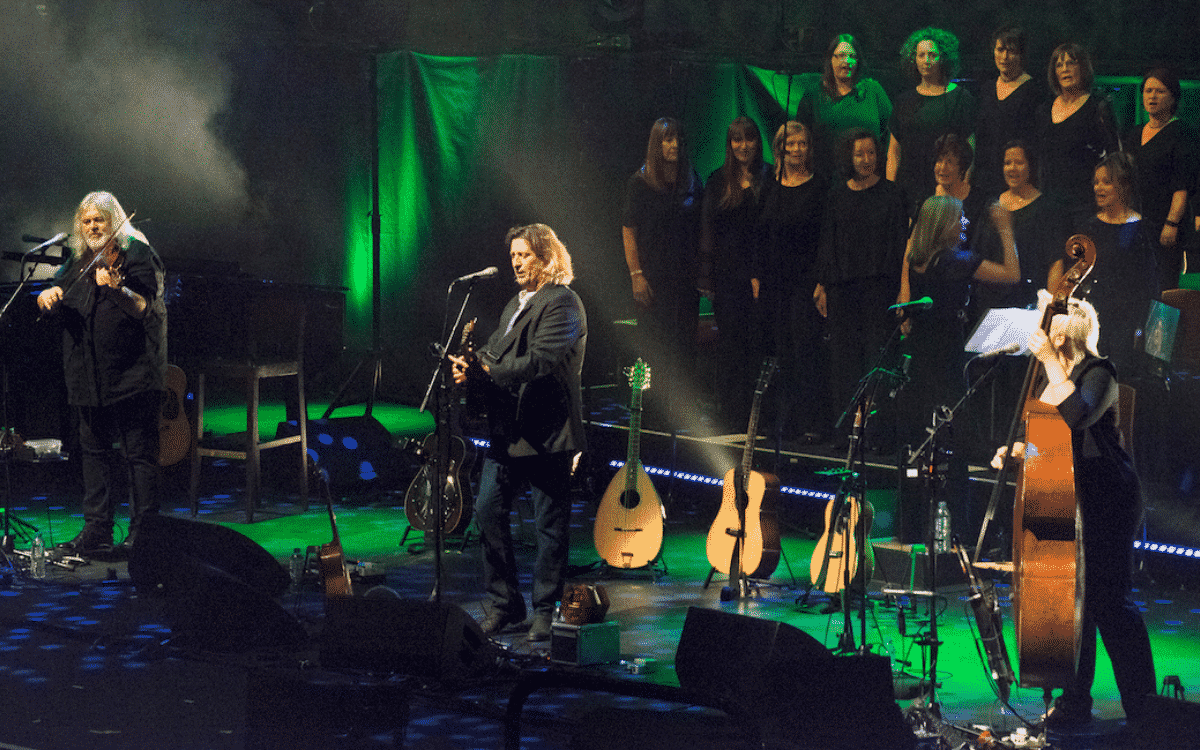

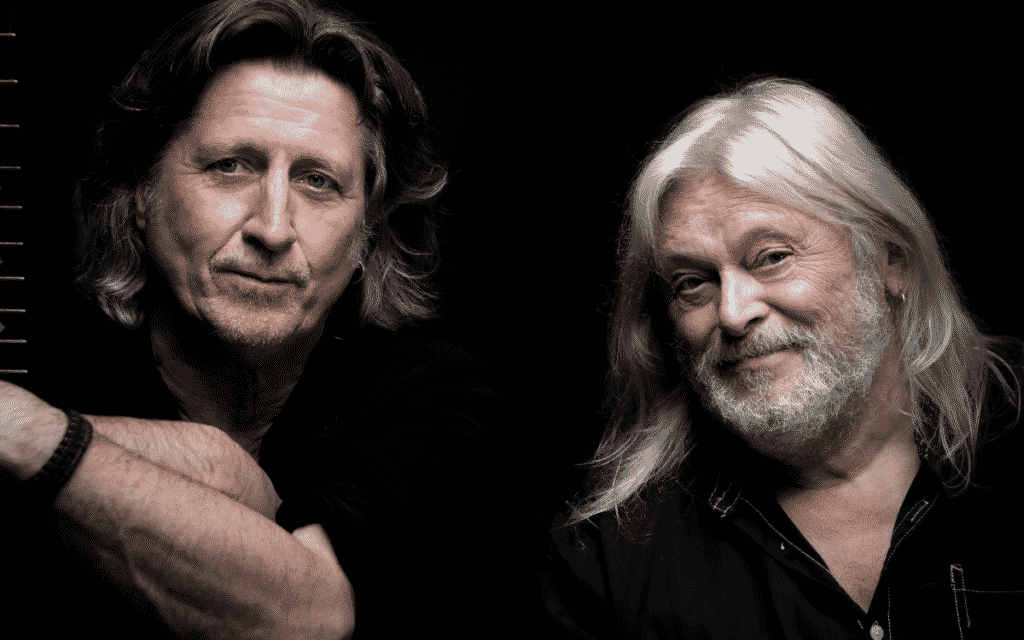

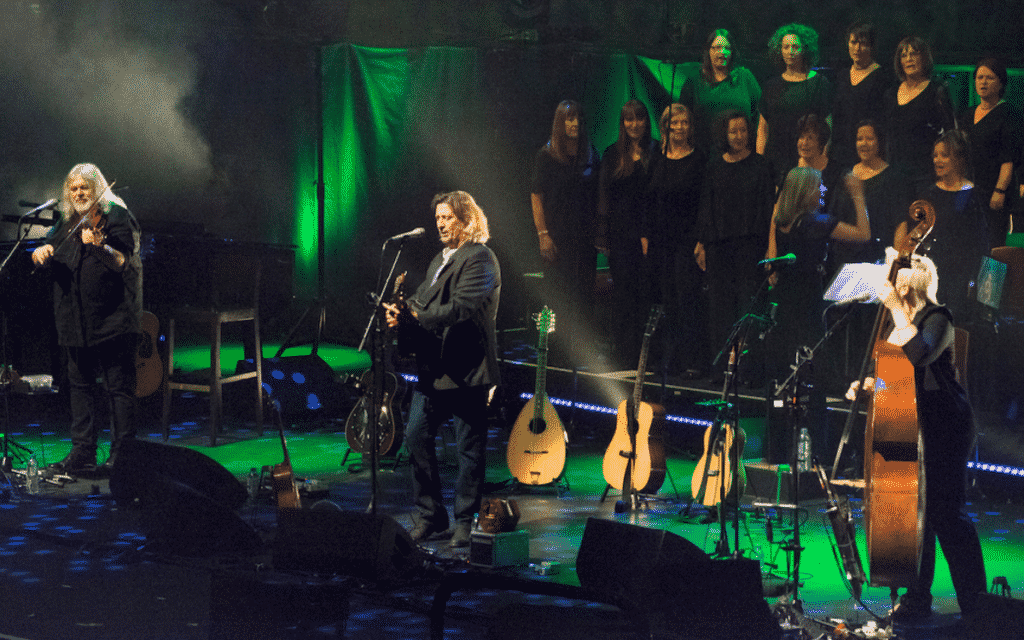

Just in time for Halloween, Show of Hand’s Steve Knightley talks to CHRIS NEWTON about ‘Hallows’ Eve’, one of the folk duo’s spookiest songs

When Richard Phillips-Jones asked me to select a song for the Spooky Isles Halloween Radio Show, there was only one song I could possibly choose.

When I told legendary folk duo Show of Hands that we had included their song, ‘Hallows’ Eve’, Steve Knightley very kindly agreed to chat to me about their spookiest song.

‘Hallows’ Eve’ is an incredibly beautiful song. I can’t think of anything more appropriately autumnal. I understand it was written by West Country composer Chris Hoban. Did he write the song specifically for Show of Hands, or did you approach him about performing it? What was it that drew you to this song in particular?

It came from socialising with Chris. He’s a Topsham resident, he’s about my age. He’s actually a music teacher. He’s possibly the best unknown songwriter I know, and he’s able to research a topic like this because he’s quite an intellectual guy and from a devout background. His father was seriously high up ecclesiastical figure in London in the Catholic church.

Chris knows his religious history, and in the course of just hanging out he played me this song, and I said “Wow, I love that!” We haven’t really changed the arrangement from how he originally played it to me. There was some debate when we recorded it about the lyric: “the worlds that part us now are twain”, about what that actually means.

I thought it should be “the worlds that unite us now are twain”, but you’d need to talk to Chris about that! It’s a great song, and you’ve just reminded me that it’s one that we should be playing round about now.

‘Mirie It Is’, one of the oldest songs in the English language, describes longing for summer in the face of oncoming cold. What I love most about ‘Hallows’ Eve’ is that it continues that time-honoured theme of our relationship to the land and the changing seasons – that idea of gathering the final harvest in “for all the hardship winter brings.” So much folklore and folk music are concerned with seasons and harvests. Show of Hands tour non-stop, it must be very hard to keep track of the days. How does life on the road affect your relationship with the seasons, which seems so integral to folk music?

Our solo tours can run from mid-January till the end of March, and the Show of Hands autumn tour will typically be mid-October to December. So, you’re talking about the most dramatic times for being aware of the seasons. You can suddenly hit spring in March and have these hot days even at Easter, and in January and February you can actually be in the snow.

Likewise, an Indian Summer can mean that, in October, you’re still actually warm, so you become aware of it incrementally. Usually, the clocks going forward or backward coincide with us touring, so it’s strange because of the landscapes we drive through in England: it’s not like being in one place and observing the changes. You can drive up north and suddenly there’s snow on the ground, then come back to the West Country and it feels like spring.

So, you’re aware of the change in seasons, but not in the sense of stillness in a Wordsworthian poetic way, when you’re watching them unfold slowly. It can be quite dramatic. You suddenly realise you’re inappropriately dressed for the weather, so you have to dig deep to get an awareness of the changing of the mood of the season.

You often introduce ‘Hallow’s Eve’ as being about the true meaning of Hallowe’en and not the “American trick or treat nightmare”. But, just like the festival’s Celtic origins, trick or treating originated in the British Isles as ‘guising’, which dates back to the 16th Century. What were your childhood experiences of Hallowe’en?

I can’t remember Halloween figuring at all when we were kids, to be honest. We weren’t living in a very rural location where we were in touch with any sort of ancient traditions. The Devon folk singer and songwriter Jim Causley is very much aware of the Devonian traditions, particularly around wassailing.

He has a collection of wassailing songs. To be perfectly honest, it was the American imposition of that idea that I became aware of. We’d like to think that we did these ancient dances around Beltane fires and all that sort of stuff, but unfortunately not! I was aware of Walpurgisnacht, but only because that’s my birthday, and I was very much into myths and legends, The Golden Bough and all that sort of stuff.

And, obviously, I was a Lord of the Rings reader. I was into my myths and legends big time, and although I was aware of all the ancient, pre-Christian, ceremonies I can’t say that they were part of the fabric of our social life growing up.

Your song ‘The Old Lych Way’ features on the same album as ‘Hallow’s Eve’. In some ways they feel like sister songs: one is about honouring the dead, the other is about the departed soul’s last request. Was this something you were conscious of when selecting songs for ‘The Long Way Home’? In a strange, slightly maudlin, way they both seem strongly connected to the idea of ‘home’.

I’d like to claim credit for ‘The Old Lych Way’, but unfortunately, it’s another one of Chris Hoban’s. He’s into his Dartmoor myths and legends, and his version was slightly different. It didn’t have that feel of a monastic procession going along a burial track that the Show of Hands version does. We slowed it down and added that the bass drum to make it sound like the gates of doom being opened! But it’s a great song. I like songs that are part of a location.

I think we started that off years ago on our album ‘Lie of the Land’, where I put a location next to every song. Whether it was about that place, or it suggested that place. I quite like that idea. I like the idea that these folk songs are collected in a particular town, in particular time, by a particular person. I think, in a way, the English have maybe lost that sense of connection with a song from a time and a place.

Irish musicians, on the other hand, can talk about a tune from Donegal or a singer from Derry, and they know there’s a type of fiddling or singing or a type of song that’s connected to a town or a region. We don’t seem to have that same connection. Although, there are pockets… in Northumberland and various other places.

In the course of all our touring – and even when I was doing lots of pub work in the early days before I was fully professional – in the West Country and Sussex area, and the Midlands and in London, I don’t think I ever heard what you could say was an ‘authentic’ folk performance apart from once. Just near Crewkerne on the Somerset / Dorset border; in a little pub called The Winyard’s Gap, this farming family started singing ‘Touched Her on the Toe’, and then the sister stood on the table.

This was obviously a song that this family played and sung, so it was genuine folk tradition happening in front of you, un-self-consciously. But I don’t think, apart from that, I’ve actually heard an example of that sense of place. I was actually awarded an honorary doctorate of music by the geography department at Plymouth university, because of that connection of music to location, which was quite flattering.

Maybe it will build up as the nation state fragments into component parts: as the Scots go their way and the Welsh get their identity more established, maybe the English and the regions will do the same and we will plunder our history to find stuff to express that. Not in a jingoistic or patriotic way, but just to feel rooted. That’s what I’ve always tried to do as a writer: to try and have a sense of place. ‘World Music from the West Country’, that was our strapline!