The infamous 1804 Hammersmith Ghost case, a tragic result of mistaken identity leading to a fatal shooting, exemplifies the historic intersection of ghost stories and English law, says guest writer NAOMI RYAN

Christmas wouldn’t be Christmas without a ghost story, and everyone has their favourite yuletide ghoul.

Whilst Dickens may have created the best-known Christmas ghosts, Montague Rhodes James (Monty to his friends and fans) is responsible for some of the greatest festive frights in ghost story literature.

Ever since that cold winter evening in 1893, when he delivered his first two ghost stories to the eager audience of Cambridge’s Chit Chat Club, Monty’s stories have been a defining and beloved part of Christmas, scaring each generation in a different way.

Between 1904 and 1935, his published stories were not only instant bestsellers but instant classics, with his genius being recognised almost immediately by critics and the wider public alike.

Between 1971 and 1978, the BBC’s exceptional A Ghost Story for Christmas series reintroduced Monty’s tales to a new audience, resulting in an entire generation being terrified of twisted bedsheets, and the BBC’s 2004 decision to revive the tradition of Christmas ghost stories has kept today’s generation scared of mysterious whistles, vanishing rooms and apparently unprepossessing mezzotints.

Monty’s Terrifying Trials

Monty was a precocious academic, a gifted medieval scholar and talented educator. He also had a deep interest in the English legal system, which can be spotted in his ghost stories.

In The Ash Tree, Sir Matthew Fell participates in the trial and execution of Mrs Mothersole for witchcraft, only for him and his heirs to be tormented and killed by her vengeful spirit. Not only is the story inspired by the real witchcraft trials of the 1600s, but could Matthew Fell’s character have been inspired by two famous legal Matthews, either Matthew Hopkins, the self-declared “Witchfinder General” or Sir Matthew Hale, a Lord Chief Justice who presided over several witch-craft trials?

In Martin’s Close, a ghost avenges her own murder by tormenting her murderer. The story is presented as a trial transcript and the trial is presided over by the very real (and infamous) 17th century judge, George “Hanging Judge” Jeffreys, who earned his ominous nickname through his involvement in the Bloody Assizes, a series of trials in the West of England that followed the unsuccessful Monmouth Rebellion and resulted in the execution or transportation of in excess of 850 people.

In A Neighbour’s Landmark, the classic Monty hero – a book loving antiquary, encounters the screaming ghost of Lady Ivie, aka Theodosia Bryan, who was tried for forgery before the aforementioned Judge Jeffreys. Monty even wrote a preface to a non-fiction book about the trial by Sir John Fox.

Creepy Criminal Justice

It is easy to understand why Monty enjoyed peppering his ghost stories with a sprinkling of criminal justice. Tragedy, suffering and brutality have always been at the heart of the English legal system, whether it be the injustices of witch trials, the indiscriminate cruelty of the Bloody Code or the sinister torment of the death penalty. This bloody history also explains the prevalence of legal ghosts and legends.

Ghostly footsteps are often heard at the Old Bailey. Lancaster Crown Court, located inside Lancaster Castle, is said to be haunted by the ghosts of hundreds of men and women hanged on the grounds. No surprise, considering that Lancaster Assizes sentenced more people to death than any court outside London.

Even the relatively modern Leeds Crown Court is said to be haunted by a friendly ghost called “Fred”, whilst multiple courthouses in the West of England claim to be haunted by the ghost of Judge Jeffreys himself, thanks to his involvement in the Bloody Assizes. Needless to say, the dark history of the criminal justice system has left its mark on many legal locations.

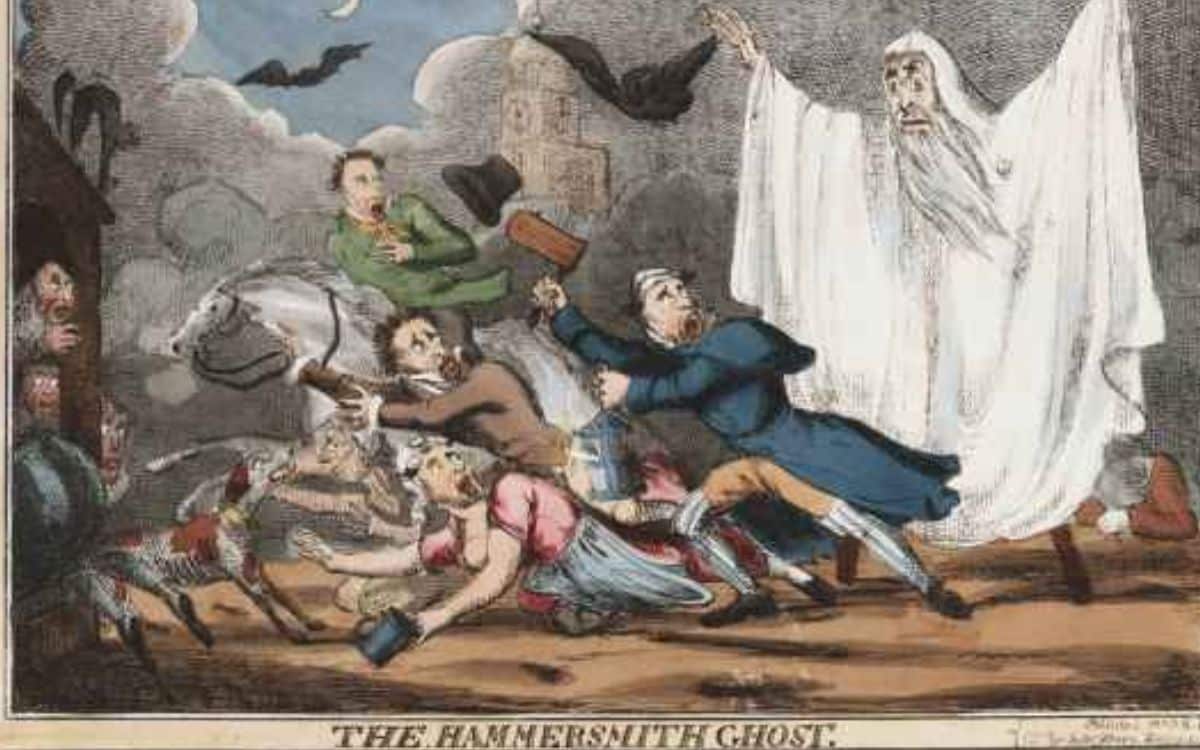

Haunted Hammersmith

But ghosts do not just haunt courthouses. Occasionally, they haunt the very trials themselves. Perhaps the most influential legal ghost story occurred in Hammersmith in 1803. That Christmas, the then quiet little village was alive with rumours of a ghost, with the encounters spanning the ridiculous to the genuinely threatening. Some witnesses described seeing a white-sheeted spectre jumping out from behind gravestones in St Paul’s Churchyard, whilst rumours abounded that a heavily pregnant woman had died of fright after being attacked by the spook.

Fear spread through the local community, and at least one man, Francis Smith, decided that the best solution was to hunt down the ghost. He started to patrol the streets, armed with a musket. On the evening of 3 January 1804, he finally encountered the dreaded monster. At the junction of Black Lion Lane and Beaver Lane (a junction that you can still visit, if you feel brave enough!), he saw a figure dressed in white.

Terrified, he shouted “who are you, and what are you? I will shoot you!” He received no response. Instead, the figure turned and approached him. Struck with fear, Smith fired, vanquishing the ghost. Or so he thought. In reality, he had shot dead Thomas Millwood, a local bricklayer who was walking home after visiting his family.

The Macabre Old Bailey

Realising his mistake, Smith became hysterical and immediately surrendered to the local watchman. 19th century justice was swift, and his trial started at the Old Bailey on 11th January 1804, a mere 8 days after the shooting.

Situated at the edge of the City of London, the Old Bailey hears the most serious and important trials in the country. The current building was opened in 1907, but a courtroom has stood on the site since the 16th century. It is built on ground steeped in blood and terror. Not only was it built beside the legendarily grim Newgate Prison, but it is close to two notorious sites of execution.

From 1783 to 1868, around 1130 people were publicly hanged outside the courthouse itself and the nearby St Sepulchre-without-Newgate still displays a bell that that was rung outside the condemn man’s cell on the eve of an execution. Walk approximately 100m from the entrance to the courthouse and you’ll find The Elms, Smithfields.

Now a meat market (rather ironically), between 1305 and 1612, it was the site of gruesome executions. Heretics were burned alive and traitors were hung drawn and quartered on the site. A plaque commemorates the many victims of these terrible punishments, including William Wallace, Wat Tyler and many Protestant Martyrs.

The Trial: Can you murder a ghost?

It was in this austere but bloody courthouse that Francis Smith stood trial for the murder of Thomas Millwood. The trial was presided over by the Chief Baron of the Exchequer, Sir Archibald Macdonald: a very senior judge. The prosecution case was simple: Mr Smith was guilty of murder because he had deliberately shot dead Thomas Millwood. Mr Smith’s defence was equally straightforward, he was not guilty because he did not believe he was killing a person. Rather, he truly believed that he was shooting the ghost that had terrorised the locals of Hammersmith. The Old Bailey still holds the records of the trial.

To build their case, defence counsel asked the witnesses about the alleged ghost. All were willing to confirm that a ghost was prowling the area. Indeed, many claimed to have seen it! One local resident, a watchman called Mr Girdler, described seeing the ghost whilst on patrol. “It” (rather than he…) was wearing a white sheet or tablecloth. John Locke, a local wine merchant, gave the ghost a more unusual appearance. Occasionally he appeared in white, but he also appeared in the skin “of a beast”, something like a calf skin.

It was even suggested that the ghost may have had horns. These accounts conjure up a rather absurd image of the ghost, but some descriptions were more menacing. A local brewer, Thomas Groom, described being attacked whilst he walked through St Paul’s graveyard. The ghost grabbed him by the throat and scuffled with him, only releasing him when he bit the ghost’s hand.

Having established the almost febrile and fearful atmosphere that had enveloped Hammersmith during Christmas 1803, defence counsel presented the second string to the defence bow: Mr Millwood looked like the Hammersmith Ghost. Under cross-examination, one witness agreed that Mr Millwood’s work clothing – white linen trousers, a white flannel waistcoat and white apron – was very similar to the clothing allegedly worn by the ghost. Another witness said that Mr Millwood had been confused for the ghost shortly before his death. That witness even admitted warning Mr Millwood that he should wear a grey coat to avoid being confused with the ghost again.

So in short, the defence was attempting to argue that Mr Smith mistakenly but genuinely believed that he was killing a ghost and not a person, and that this made him not guilty of murder. However, this defence was doomed to failure. As recorded in the Newgate Calendar, the judge made it clear to the jury – it is not a defence to kill a person you believe to be a ghost, because it is not reasonable to believe in ghosts.

The jury retired to consider their verdict, and they must have been feeling very sympathetic to Mr Smith, because they attempted to return a verdict of manslaughter, not murder. The judge made it clear that the verdict was not available. He stressed to the jury that if they accepted the facts as they had been presented (and arguably accepted by the defence), then Mr Smith was clearly guilty of murder. As a matter of law, his belief that he was killing a ghost was irrelevant because it was unreasonable. Having received that direction, the jury convicted, leaving Mr Smith to face the only penalty available at the time: the hangman’s noose followed by public dissection.

However, Mr Smith would be spared the noose. His case had become quite the cause celebre, and the judge told the jury that he would report it to George III and invite him to exercise the royal prerogative of mercy. George III duly commuted Mr Smith’s sentence to one year’s hard labour, reflecting the wider view that this was a highly unusual offence that did not warrant execution.

The Legacy of the Hammersmith Ghost

The case was never appealed, so strictly speaking, it never became a binding legal authority. For many years, the law remained clear: the defence of mistake was only available if the mistaken belief was both reasonable and genuinely held. But in 20th century, the law evolved and became more willing to allow a person to rely on the defence of mistake even if their belief was wholly unreasonable. This means that had Mr Smith committed his crime today, he may have had a far better chance of an acquittal than he did in 1804.

As for the Hammersmith ghost itself, the court case appears to have exorcised that spirit. Shortly after the shooting, a local bootmaker admitted to being the Hammersmith ghost, claiming he had simply done it to scare his grandchildren. No action was taken against him.

Whilst the Hammersmith Ghost returned to his grave, the 1800s would see many more outbreaks of supernatural hysteria. Not only would it be the century of Spring Heeled Jack: the mysterious, fire-breathing high-jumper, but it would also be the century that saw regular outbreaks of ghost hunting mobs.

As summarised by Roger Clarke in his excellent “A Natural History of Ghosts,” ghost hunting became a popular Victorian fad. In Bermondsey in 1830, 2000 people surrounded a house in Grange Road, expecting to see the ghost of a dead clergyman. In 1865, mobs descended on St George’s Church in Southwark in the hope of spying a ghost, and in 1895, the residents of Hackney became so fearful of a ghost in their graveyard that they took to patrolling the streets.

Press reports claimed that at least 6000 attempted to break into the local church to catch the ghost, causing a stampede that left many injured. However, whilst there were regular outbreaks of supernatural hysteria, there were no further deaths, and to this day, Thomas Millwood remains the only person to have been killed for being a ghost.

NAOMI RYAN is a barrister. After completing the BCL at St Catherine’s College, Oxford, she taught criminal law to undergraduates at St Hilda’s College Oxford and University College London before embarking on her career as a criminal barrister. She both prosecuted and defended before moving to work for as a civil service. She has worked for an array of prestigious departments, including the Attorney General’s Office, the Director of Public Prosecutions and the Court of Appeal, and she continues to work as an advisory barrister on criminal matters.

When she isn’t advising on criminal matters, she delivers talks on the more macabre side of legal history. She is a regular feature at London’s Month of the Dead festival, and can often be found addressing museums and other legal and supernatural organisations on the topic of ghost law. She plans to finish her book on the subject next year.

Find Naomi on Instagram @spooky_barrister