From Beltane to Halloween, ZOWIE SWAN explores the fiery legacy of Teanlay Night on Lancashire’s Fylde Coast

The Fylde Coast of West Lancashire is a seemingly inconspicuous place. Thirteen miles of windswept coastline, cradled by Morecambe Bay to the North, the Ribble Estuary to the South, the Irish Sea to the West, and the Bowland Fells to the East.

Its brightest bauble is most likely the famous pleasure hub of Blackpool, which asserts part of this coast for its celebrated Golden Mile, filled up and down with gaudy amusements, noisy arcades, and dazzling illuminations.

Yet, before the Georgian sea-bathers and the Victorian entrepreneurs came to claim the town as their own, there was already a rich and archaic pre-Christian culture haunting the dark corners of the Fylde.

Halloween itself is now known the world over, thanks to the far-reaching fingers of North American pop culture.

From Jack-o-lanterns and monster masks to trick-or-treating, the rise in popularity of the North American Halloween has seen many of these practices adopted by people throughout the Western world.

However, in Britain, instead of an assimilation of new practices and ideas, it could be more accurately described as a return to ancestral rites. Many of these familiar modern customs were observed throughout the British Isles, and certainly across the Fylde Coast, for many hundreds of years, before being driven out by disapproving Victorian moralists.

The meaning of present day Halloween is slightly murky, with some unfairly dismissing it as little more than a carnival of candy and consumerism.

Like many ancient festivals, the original purpose is easily lost over time. We often hear Halloween described in film as ‘the time when the veil is at its thinnest’, but what does this actually mean?

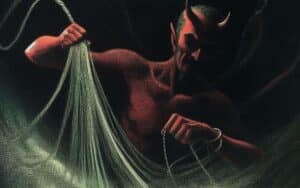

Well, it was believed that when the sun set on Halloween night, it entered the gates of Hell itself and all the spirits and creatures of the underworld were free to slither out and terrorise the living until the sun rose once more. This idea of the dead walking the earth predates zombie films by millennia.

In Cassell’s Dictionary of Superstitions, Halloween is described as ‘the blood-chilling idea that on this date the souls of the dead make their way back to their earthly homes to warm themselves at their old firesides’ (Pickering, 2002).

Teanlay Night on the Fylde Coast

Enter the people of the Fylde Coast and their old tradition of Teanlay Night. This is a belief that has deep roots, tracing back to the Celtic festival of ‘Beltane’, which is still observed in some areas of Ireland and Scotland. The origin of the word Teanlay is Gaelic, from the old tongue once spoken in Lancashire, with teine meaning fire and lae meaning day (Davies, 1883).

The mummery of the Teanlays involved the burning of great bonfires atop stone cairns across certain hallowed points of the Fylde. The custom was something straight out of folk horror, being described as ‘simple in its performance, and [consisting] merely of a circle of men raising masses of blazing straw on high with pitch-forks’ (Porter, 1876).

At Poulton-le-Fylde, there was an old meadow known as the Purgatory field. On Teanlay Night people from across the Fylde plain would gather in this field around the bonfire or bone-fire, where bones and stones would be roasted in offering.

These white stones, ‘which at first had circled the fire, were thrown into the ashes, and being left all night, were sought for with anxious care at sunrise, when the person who could not distinguish his own particular boulder was considered, i.e., some misfortune would happen to him during the course of the ensuing year’ (Thornber, 1837).

The light of the Teanlay flames was thought to guide the souls of loved ones, who had departed in the last year, out of purgatory into the next life. Also, the fire would keep those in its presence safe from the mischievous and malevolent spirits that walked abroad that night. It is thought that the farmers, those shadowy men with their uplifted bundles of burning straw, sought to also protect the crops from failing in the coming year by making their Teanlay offerings on this night.

The only surviving memory of the Purgatory field today is that of the nearby modern-day Teanlowe shopping centre, which borrows its name from Teanlay Night. Other notable Teanlay fires were burnt on the great peat-laden moss of the south Fylde, in what is present-day Marton.

The Fylde Coast Teanlay celebrations of 300 ago may have involved other familiar motifs of our 21st-century Halloween.

- Pumpkin lanterns originate from the carved turnip lanterns that were lit to guide the dead. These lanterns mimicked that carried by Jack-O’-Lantern, the doomed Irish spirit cursed by the Devil to walk the night for eternity, led only by the flickering flame of his lantern. Grinning turnip lanterns would have adorned the doorways and windows of the Fylde villages and hamlets.

- Halloween costumes come from the disguises or cloaks people would wear to go ‘guising‘, covering themselves up so the goblins and boggarts wouldn’t recognise them. Wearing a mask or painting your face meant you would go unnoticed by the spirits.

- Trick or Treating stems from the tradition of ‘souling’, where bands of children would go from door to door, singing songs for the reward of spiced soul cakes or harcakes, which were pauper cakes given in charity.

- Parkin was eaten at this time of year, just as we do now. It was made from treacle and oats because oats were in surplus due to the annual grain harvest at the end of October.

- Magic was always connected to Halloween. The rural folk of the Fylde performed rituals with apple cores or peel, to tell their fortunes or see the initials of their future lovers in the fallen peel.

- Witches were feared on Halloween. The people of Lancashire would light ‘witch candles’ and walk up into the fells to ‘late’ or ‘leet’ the witches, a word derived from the Saxon ‘leoht’ meaning light. This was thought to offer protection to the community from witches for the following year.

There is a reason why Halloween endures. The compulsion to celebrate at this time of year, to honour the dead, and to take delight in being scared, is not an alien concept at all. The cultural phenomenon of the North American Halloween in fact teaches us what we have lost about our own past.

On the last night of October, the people of the Fylde Coast firmly believed in the importance of remembering the dead, for by doing so we can appreciate those who still live.

This Halloween, whatever you choose to do, remember those that you have loved and lost. Wrap up warm, take your lantern, eat your parkin, don your disguise, stay close to the light, and have a magical Teanlay Night.

Tell us your thoughts on Teanlay Night in the comments section below!