Walpurgis Night – 30th April – is a spooky event named after a British saint. It’s celebrated all over Europe but ironically it’s not widely known in the UK. Guest writer MJ WAYLAND reports.

Every year this date is celebrated by pagan religions across Europe, the veils between this world and the next are delicate and the time is right for magick and other occult activities.

Surely I’m talking about Halloween? Actually I’m talking about Walpurgis Night on 30th April.

What is Walpurgis Night?

As with most European traditions, Walpurgis Night has roots in ancient pagan customs and festivals. Most festivals on 30th April celebrate fire and the coming of the spring. This fire festival has an incredible evolved existence that only now are anthropologists beginning to understand, indeed Pauline Bambry from the University of Wales recently admitted that she believed the festival dates from prehistory.

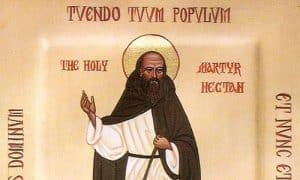

The name Walpurgis surprisingly originates from a very different source, that of a Devon-born nun called Walpurga who become known for speaking out against witchcraft. Since the time of her canonisation and the Christianisation of many festivals across Europe, the night before her celebration day became known as “Walpurgis Night.” It is at this time that the night obtained some of its many negative aspects, when it was believed, like Samhain/Halloween, that ghosts, spirits, demons and the devil had free reign to walk the earth.

In Scandinavian countries, a tradition dating back to Viking times (and possibly further) is observed by the building of very large bonfires on hills and mountains, it was thought that the power of the fire would scare away evil spirits or predators, or possibly both.

In Southern Sweden, a long known custom is of younger couples collecting greenery, branches and leaves from the forest at dusk. The couples would adorn the houses of the village and take part in festivities relating to the forthcoming Summer.

This tradition is similar to that of one that exists in Britain, where young couples would ‘tie the knot’ on 30th April and have 366 days to make the romance succeed, before untying the knot the following year.

In the British Isles the 30th April is honoured as one of the cross points of the neo-pagan calendar and known as Beltane, and shares similar traits with their European neighbours such as celebrating fire and the coming of Spring. In medieval Ireland there are records of huge ‘Bealtaine’ fires in Central Ireland and also at a number of ancient prehistoric sites. Many customs that take place have links with European neighbours and are well known across the Isles, these vary from the May Pole and crowning of the May Queen.

Across the world many pagans, wiccans and celtic traditionalists will be casting circle, performing ritual and above all celebrating the element of fire on April 30th or there abouts – magick is alive and well.

In film and books, Beltane and Walpurgis Night have been portrayed in many diverse ways.

The unforgettable film “The Wicker Man” was no doubt influenced by the records of Julius Caesar indeed the film’s screenwriter, Anthony Shaffer was intrigued by the reports that the Gauls and Celts burning criminals in a large wicker figure at the start of Spring.

Dracula, a truly European vision of horror has a number of links with Walpurgis night. In the short story “Dracula’s Guest” takes place on Walpurgis Night. Stoker wrote, “Walpurgis Night was when, according to the belief of millions of people, the devil was abroad – when the graves were opened and the dead came forth and walked. When all evil things of earth and air and water held revel.”

Later in the 1931 film “Dracula”, at beginning of the film a Romanian peasant describes the night as Walpurgis Night and Dracula’s clerk Renfield arrives at Dracula’s castle at midnight, the beginning of the witching hour.

So if you miss your Halloween spookiness and horror, then why not take part in the Beltane / Walpurgis Night festivals and light a bonfire, crown a Queen and then dance around a pole! Or you could just sit at home and watch “The Wicker Man”.

Walpurgisnacht, Witch Hunting, Returning Saints and German Imports

(Article originally published on Spooky Isles on 21 April 2013.)

JON KANEKO-JAMES loves Walpurgis Night – the second most spooky night of the year!

Walpurgisnacht, night of witches. I’ve always celebrated it, even before becoming involved in the esoteric and occult. Why? Well, perhaps the less than salubrious reason that when I was about 11 BBC One had a horror night presented by a Crypt-Keeper-like puppet called ‘Dr. Walpurgis’ who caught my imagination and filled it with images of magic and witches.

The real Walpurgis Night, as you might imagine from the name, is a Germanic and Scandinavian holiday. The name of the festival is almost certainly a Christianisation of an older Pagan holiday: since it’s named after Saint Walpurgis, a British missionary from Dorset. The beautiful Saint is said to have travelled what is now Germany, healing the local Pagans with her miraculous powers and converting them to Christianity.

The festival has a lot in common with its British Pagan counterpart, Beltaine: it’s the ‘antipode’ of All Hallows (Samhain, in the Ancient Celtic calendar,) celebrated on the 30th of April and the 1st of May, exactly six months before All Hallows on the 31st of October and the 1st of November.

Even now, in Finland, Germany, Sweden and the Netherlands people gather around bonfires to drink, party and drive off the darkness.

Both festivals, Beltain and Walpurgisnacht, were traditionally times when the spirit world was thought to be closer than ever. The Ancient Celts would gather together in forts like Emain, Ulster, where they would gather under the protection of Druids as they first ritually extinguished every fire in the Kingdom, and then restarted them in a magical ritual felt to drive away the darkness and restart the year.

For the Celts, Beltain was also the start of the year for the Tuatha de Dannan, the ancient and mysterious race who had been driven underground.

Also, like Walpurgisnacht, Beltain later became associated with witches. The nights were still long, and the renewing effect of the festival was contrasted with the darkness of the night before.

In a time before our much-prized modern ‘rationality’ (plus the fact that we now have roads, policing, streetlights and fewer large wild animals) there was still a lot to be afraid of in the darkness.

Not only that, but by the late 15th Century there was a new storm brewing in Germany. Church thinkers had gradually been getting more hard-line on the matter of witch finding.

Catholic thinkers were chafing more and more against the idea that witches were brewing drugs that would help woman to abort unwanted babies, but there was also a strong skeptics movement, like the Inquisitor of Milan who investigated a prominent witchcraft case where suspects wove a tale of magic, curses and transmogrification.

The Inquisitor, unsure what to do, and more than a little unbelieving that such things were possible, eventually admonished the two women for superstition and released them with a minor penance.

Unfortunately, there were others. Bernardino of Sienna, wrote condemning a witch who had confessed to killing no less than thirty infants by bleeding them.

More significantly for The British was a German from around the Saltzberg region: Heinrich Kramer. Kramer was an invetrate Witch Hunter, a believer in hardline thinkers like Bernardino and Johannes Neider.

He believed in the Satanic nature of Witches, the idea of Witches holding Sabbats at magically significant parts of the year and the horrible lists of transgressions already appearing in German Witch trials.

The problem was that Kramer was already in trouble: at home he was being called a ‘senile old man’ and some were questioning his right to prosecute witches (especially since there was a long tradition of European secular law stating that there was no such thing as witchcraft, and that anyone who killed a witch was committing nothing but murder.) Kramer’s defence was to get together with Joseph Sprenger, his sometime partner, and pen the Malleus Maleficarum, or Hammer of Witches.

The book was a manual to ‘educate’ magistrates on the danger of witches, and for a time it was treated with the contempt it deserved. Unfortunately, times were changing: the Reformation was sweeping Europe and even the Catholic Church was becoming more hardline.

As new Protestant governments started to fear a Counter-Reformation they needed to find a way to crack down on what were seen as the superstition and idolatry of Catholicism. They needed to wipe away the existing order if their new religion was to survive, and since Catholicism had gradually meshed with various folk-traditions and ‘old ways,’ the answer suddenly seemed to take hold: to unite the forces of this new Christianity around opposition to the massed legions of Satan.

The Witch was characterised, the crimes were drawn up: witches could change shape and fly on various household objects (brooms are mentioned, but the earliest reports talk about colanders as being more common.) Witches killed babies, drank their blood, worshipped Satan and engaged in horrific orgies of degrading anal sex with demons. Witches killed, maimed, stole and had spirits called Familiars that gave them direct access to the powers of Satan.

And it was now that the radical thinking of Kramer’s Malleus took hold.

The proliferation of the printing press around Europe had already ensured its survival, with the Gutenburg Press and other companies making sure that it became a popular book. It’s how-to style was ideal for authorities who needed a ready-made blueprint on how to prosecute the armies of Satan.

The Malleus came to Britain in the 1520s, largely as the result of the work of a group of clergymen and thinkers who included Henry Goodcoal, a protestant writer who condemned children for attending alleged Sabbats with their parents. Henry VII’s Reformation marked the beginning of a particularly bad time for British witches. Before, Britian had executed an average of one witch per year and had done for hundreds of years.

After the Reformation the numbers started to climb steeply: new protestant thinkers persecuted Witches for superstition and Catholicism, for murder and mind control. When Mary took control she persecuted the protestants, but the level of witch trials continued to rise. Elizabeth was no better. It’s a matter of irony that by the time Shakespeare wrote his play Midsummer Night’s Dream, Elizabeth’s religious agents were trying to suppress and criminalise traditional solstice celebrations.

It was later, under James I that the Kramerian ideas took the strongest hold. James was an avid Witch Hunter himself, presiding over a brutal period of witch persecutions in North Berwick that had taken the lives of more than seventy people.

He had written his own book on Witches, Daemonology, that advocated torture and trial by ordeal as acceptable methods for hunting witches. He was also no stranger to the ‘Malleus.

It was now that Britain had fully imported the Germanic, Kramerian idea of the witch: the ugly hag, flying through the night, cursing and murdering with magic. Our Beltain had become their Walpurgisnacht.