John Baskerville’s tale is a gripping blend of typography, haunting history and a surprising link to Sherlock Holmes’ legendary adventure, writes ANDREW HOMER

Any mention of Baskerville, and most people naturally think of Sherlock Holmes and the Hound of the Baskervilles rather than Birmingham, even though there is a connection.

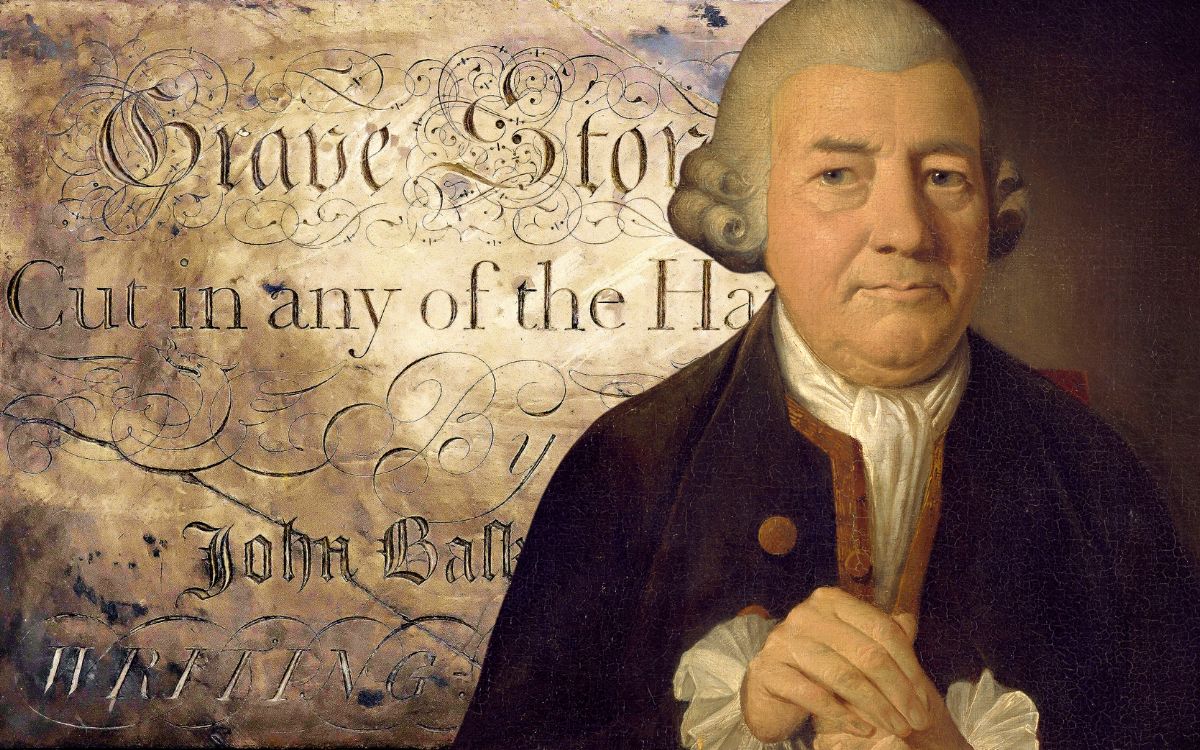

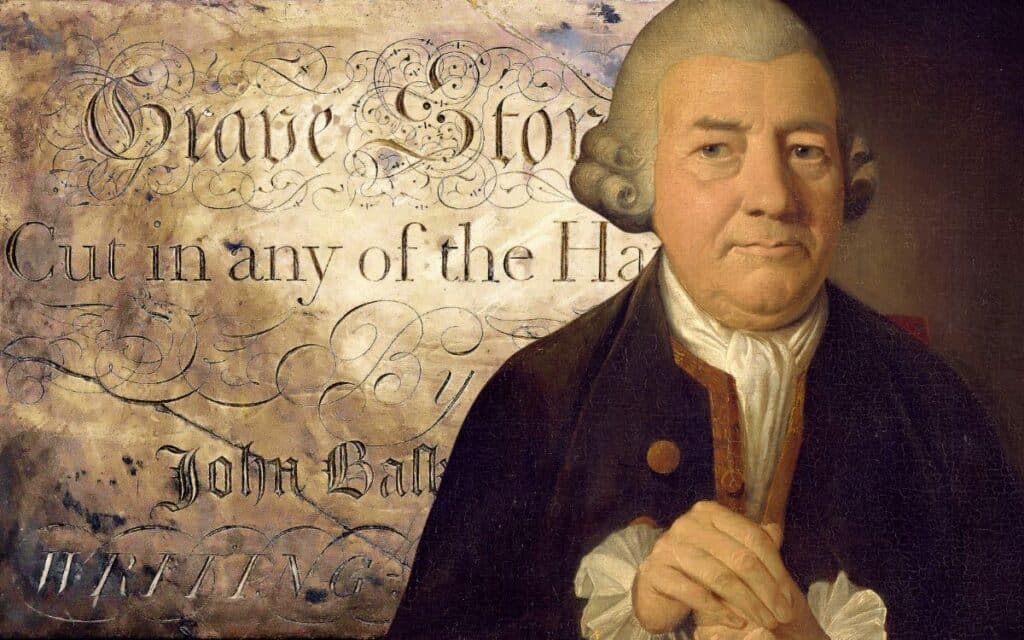

The Birmingham Baskerville, though, is John Baskerville, who is best known for designing his Baskerville typeface in 1757. This font is still in common use, and there is almost certainly a copy on your computer or laptop.

Who was John Baskerville?

John Baskerville was born in Wolverly, Worcestershire, and from 1726 was teaching handwriting in Birmingham. He later applied this skill to the carving of graveyard headstones before starting a very successful japanning business, which was an early form of enamelling.

By all accounts, he was a flamboyant, if not eccentric, character who favoured brightly coloured clothes even when conducting business. Caring little for the conventions of the time, he was a committed atheist and lived openly with Sarah Eaves, whose husband had left her, although they did marry after he died. His carriage was as flamboyant as the man himself, with finely japanned panels featuring naked cupids and flowers drawn by two beautiful cream-coloured horses.

He made his fortune from Japanned ware, which enabled him to turn his attention to his first love, typography and printing. If anything, this venture proved even more successful as he developed improved inks and printing presses to complement his Baskerville typeface. For an atheist, it is ironic that one of his best-known printed works was a magnificent folio edition of the Bible.

On the back of this success, John purchased an eight-acre estate at Easy Hill in Birmingham and had a large house built. Although no longer there, the land is now occupied by the Hall of Memory and Baskerville House, a former council building in Centenary Square.

Before his death in 1775, John Baskerville left strict instructions that his body must not be interred in consecrated ground. Instead, he had the conical base of an old windmill in the grounds of Easy Hill House converted into a private mausoleum. His epitaph, written by Baskerville himself, left no doubt as to his atheism:

STRANGER—

BENEATH THIS CONE IN UNCONSCRATED (sic) GROUND

A FRIEND TO THE LIBERTIES OF MANKIND

DIRECTED HIS BODY TO BE INHUM’D

MAY THE EXAMPLE CONTRIBUTE TO EMANCIPATE THY MIND

FROM THE IDLE FEARS OF SUPERSTITION

AND THE WICKED ARTS OF PRIESTHOOD

This should have been the end of the story, but John Baskerville’s body was not allowed to rest in peace. After his wife Sarah died in 1788, the house passed to John Ryland, a religious dissenter.

During the Birmingham (Priestly) Riots of 1791, it was stormed by a mob intent on destroying the house in the name of ‘Church and King’. Some of the rioters, however, were far more interested in the contents of the wine cellar. So much so, they failed to realise that fellow rioters had set the house on fire. The ensuing inferno trapped them inside with no hope of escape.

Since then, the atmosphere in the cellar of the 1930’s-built Baskerville House on the same site has been known to change, with people experiencing feelings of intense fear for no apparent reason. A group of three ghostly figures has also been seen on occasion. Thankfully, they are only seen as shadows, given their gruesome deaths trapped in the cellar of the blazing building. Ironically, the rioters targeted the homes of dissenters in the name of religion and a supposed support for the French Revolution, something that John Baskerville, as a committed atheist, would have deeply deplored.

On the death of John Ryland, his son Samuel leased the land to Thomas Gibson, who set about cutting a canal. During this time, the mausoleum was taken down, but Baskerville still lay relatively undisturbed. This was to change just before Christmas 1820, when workmen digging for gravel discovered the leaden coffin but covered it up again.

According to the Freeman’s Journal of 29 May 1821 (reprinted from the Birmingham Chronicle), the coffin was subsequently disinterred in May 1821 to make way for the building of a canal wharf. It was taken to the warehouse of Gibson and Sons on Cambridge Street. Here, the decision was made to inspect the contents of the coffin, and the newspaper included a description of the body, which was wrapped in a linen shroud:

… The body was in a singular state of preservation, considering it had been under ground for about 46 years. The skin on the face was dry, but perfect. The eyes were gone, but the eye-brows, eyelashes, lips, and teeth remained. The skin on the abdomen and body was generally in the same state as that of the face. An exceedingly offensive and oppressive effluvia, strongly resembling decayed cheese, arose from the body and rendered it necessary to close the coffin in a short time.

As if this disrespectful treatment of Baskerville’s remains wasn’t bad enough, it was about to get worse. There were various reports that people were being charged to view the remains. One near neighbour maintained that 6d (six old pennies) a head was charged, while other sources claim it was 1s (twelve old pennies). After some eight years, Baskerville was on the move again. This time it was to the shop of plumber John Marston.

By this time, the body was acquiring a reputation for being cursed. A surgeon from Newhall Street had torn off a small piece of the shroud as a souvenir and placed it in his pocket. Within a few days, he was dead. There were other stories of people becoming ill or meeting with grave misfortune because of Baskerville. A piece of the shroud is stored in the Pershouse collection at the Birmingham archive together with the sketch made by Thomas Underwood in 1829. No doubt the archivists wear their protective gloves when handling the fragment of shroud. Just in case!

Understandably, John Marston and particularly his wife were keen to rid themselves of the seemingly cursed coffin. Unfortunately, this was no easy task. The rector of nearby St Philip’s Church refused, even though Baskerville’s wife was buried there. A press report was put out saying that Baskerville had been interred at Cradley Chapel, where his family had connections. This was a deception. In fact, a bookseller called Nott said it would be an honour to have him in his family vault at Christ Church in Birmingham. This was surreptitiously arranged through the church warden, and the coffin was secretly interred. Baskerville was again at rest, although now on consecrated ground. It was not to last.

In November 1879, The Birmingham Weekly Post published a letter from a W. J. Scolfield that revealed what had actually happened to Baskerville’s remains.

This and a lecture given by author Talbot Baines Reed on Baskerville prompted the discovery of Baskerville’s coffin at Christ Church in vault 521. It was opened yet again in front of an invited audience, which, by all accounts, was by now quite a ghastly sight.

Not only that, but it was by now an illegal act and caused quite a stir, even as it was being discussed in Parliament. Ultimately, H. H. Asquith, the Home Secretary, deemed that it would not be in the public interest to take any further steps.

Baskerville was left in peace for five years, albeit on consecrated ground, before he was on the move again. Christ Church was demolished in 1899, requiring the vaults to be emptied.

Baskerville’s coffin was among many others that were re-interred at Warstone Lane Cemetery. Historian Chris Upton describes how the 600 or so ‘internees’ were transferred under cover of darkness in ‘an endless procession of funeral coaches making their slow progress out to the Jewellery Quarter’. It must have been an eerie sight to behold.

Once there, Baskerville was interred again, this time in a vault beneath the chapel above the catacombs. The chapel was demolished in the 1950s, but Baskerville was this time left undisturbed.

Although there are no reports of John Baskerville haunting Warstone Lane, he would certainly have good reason. For such a committed atheist, a Church of England cemetery is the last place he would have wanted to spend eternity.

And what is the connection between Sherlock Holmes and The Hound of the Baskervilles? There can be little doubt that the subject of the curse, the hound itself, was based on the many Black Shuck or Black Dog stories.

However, at the time of W. J. Scolfield’s letter in the Birmingham Weekly Post, a young Arthur Conan Doyle was lodging with a doctor on Aston Road.

It is highly likely Conan Doyle would have been well aware of the Baskerville curse originating with the death of a local doctor. He was, after all, in Birmingham, training to be a doctor himself, and beginning to write stories in his spare time.

Tell us your thoughts on The Baskerville Curse in the comments section below!