England is a country rich with history and stacked-full of corpses. For every little headstone, there’s an enormous monolith to a long-dead duke. Yet with so many churchyards and cemeteries to wander around, it’s easy to miss some of the weirdest and most wonderful memorials the country has to offer. Guest writer KATE CHERRELL picks some of the strangest gravesites for you to visit

William Mackenzie’s Liverpool Pyramid (1794-1851)

St Andrew’s Church, Liverpool

In the middle of Liverpool, a few streets away from the bustling shopping hub sits a 15-foot high pyramid. This is the resting place of no Egyptian dignitary, but a Victorian Liverpudlian with a love of gambling.

The Liverpool pyramid has a wealth of legends surrounding its occupant. Before his death, William Mackenzie gave strict instructions that he should be interred, sat at a card table, holding a winning hand. Even more bizarrely, many believe that Mackenzie was not interred at all, but rather propped above ground, so as to cheat Satan from taking his soul.

Sadly, the reality is that the grave, containing Mackenzie and his first and second wives, is just that – a standard below-ground vault burial. However, the idea of a hunched poker-playing corpse inside a pyramid has a little more public appeal!

The Rajah Rammohun Roy Memorial (1772-1833)

Arnos Vale Cemetery, Bristol

The Rajah memorial is one of the most enormous and imposing structures within Arnos Vale and is arguably the most visited memorial, with devotees from around the world coming to pay their respects to a man regarded as being one of the fathers of modern India.

Rajah Rammohun Roy was an Indian social reformer, influential in politics, education and in religious and social reform. He is also renowned for helping to abolish practises of child marriage and

Upon a visit to Bristol in 1933, he suddenly died from suspected meningitis. Several years after his death, fellow reformer Dwarkanath Tagore commissioned and built the enormous monument, which now acts as a place of pilgrimage.

The monument is designed to mimic the traditional Bengali

Tomb of Lord Edward Pelham-Clinton (1836-1907)

Brookwood Cemetery, Surrey

Angels and grieving figures are commonplace in cemeteries around the world, however, Lord Clinton’s enormous memorial is rather more show-stopping than the average carved headstone.

Clinton was a politician, lieutenant colonel and groom-in-waiting to both Queen Victoria and King Edward VII.

Although these are impressive achievements, graves of such dignitaries are commonplace in large, city cemeteries. However, the monument itself is a true thing of beauty. The listed monument depicts a deceased woman, recumbent and draped in cloth. Beside her kneels a weeping man, mourning her death.

Above

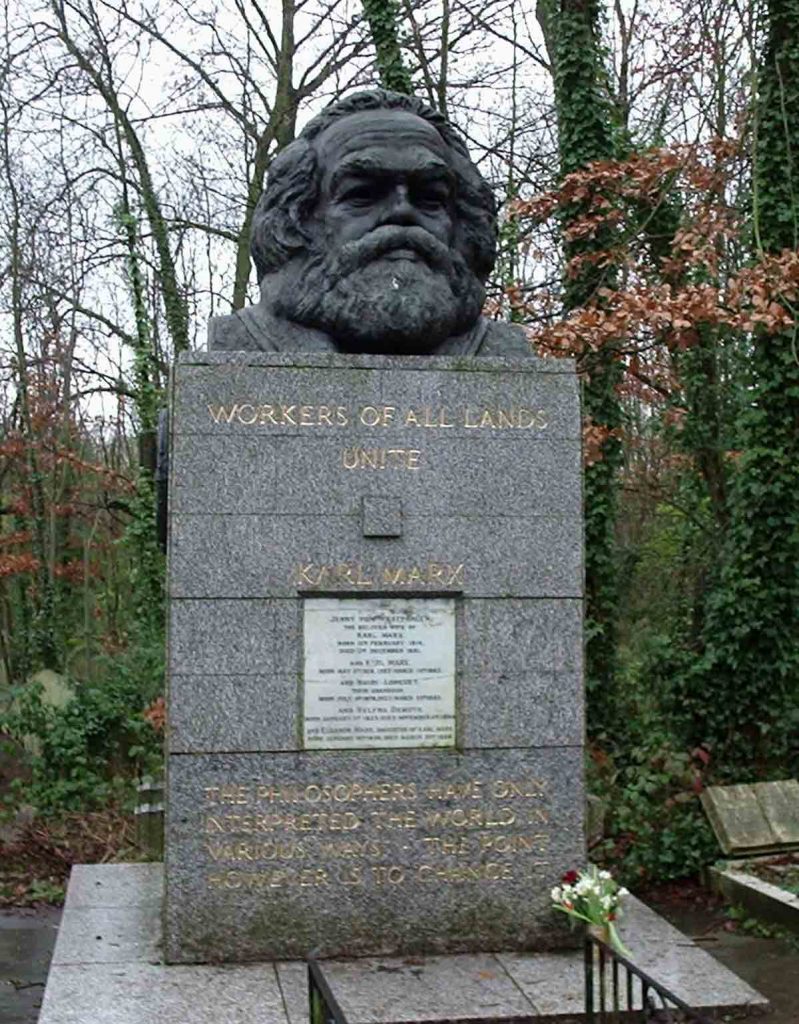

The Tomb of Karl Marx (1818-1883)

East Highgate Cemetery, London

Karl Marx’s tomb is infamous in its simplicity and enormity.

While Victorians flooded their memorials in inscriptions, weeping angels and draped urns, Marx’s supporters decided on a rather more literal memorial; a massive head. Marx, the politician, philosopher, socialist and writer of ‘The Communist Manifesto’, was born in Germany, but died in London in 1883.

Following outrage and exile as a result of his political publications, decades of Marx’s life was spent in the capital, raising children and continuing his involvement in socialist and worker’s movements. Following his death from pleurisy, Marx was interred in Highgate with a very small number of mourners in attendance.

Seventy years after the family’s internment, the Marx Memorial Committee petitioned for the exhumation and reinternment of the Marx family in a different plot, subsequently allowing the construction of the enormous memorial that sits in Highgate today.

The tomb, regarded as one of the world’s most recognisable graves, consists of a huge brass bust atop a marble pillar. The pillar is inscribed with many of Marx’s quotes, including the final line of his manifesto ‘workers of all lands, unite.’ While there was controversy in Highgate’s decision to charge an admissions fee to the cemetery, it was in part to cover maintenance costs, especially those stemming from the perpetual vandalism of Marx’s tomb.

Frank Bostock’s Lion (1866-1912)

Abney Park Cemetery, London

As far as imposing tomb decorations go, you can’t get more impressive than a life-size marble lion. Frank Bostock was a Victorian David Attenborough of sorts – educating the masses on African and Asian wildlife.

However, Bostock was a true Victorian entertainer, travelling the world with a menagerie of animals in tow, making his name

After surviving both a lion and tiger attack, Bostock’s demise came not at the paws of a big cat, but from the flu.

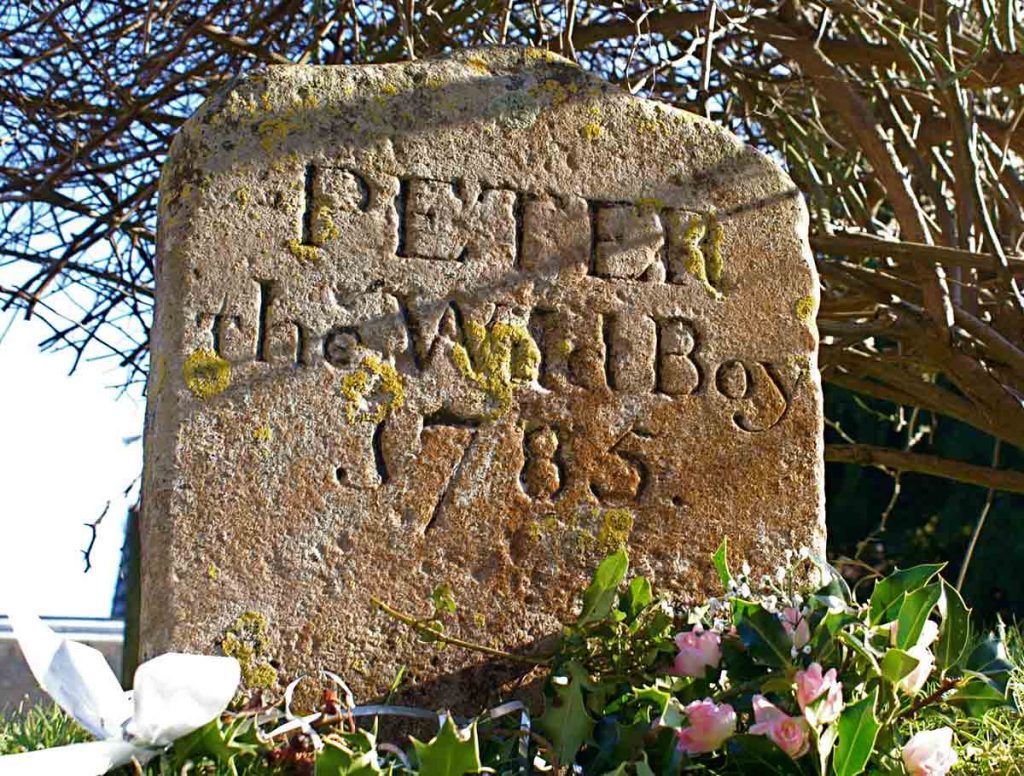

Peter the Wild Boy (1713-1785)

Hertfordshire

Found living wild in the woods near Hamelin in Germany, Peter was a ‘feral’ child. He had lived his lonely forest existence for an extended period of time, walking on all fours and surviving on a diet of wild plants.

Now believed to have been suffering from Pitt-Hopkins Syndrome, Peter quickly became quite the court curiosity.

Found by a hunting party of George I on a visit to his homeland, Peter was soon brought back to the UK, where he became somewhat of a novel ‘human pet.’

He was placed under the care of several court workers, eventually settling in a Hertfordshire farmhouse, where he lived alongside the various tenants who passed through. Peter was granted a living pension to sustain him but was never able to communicate or fully integrate into his environment.

Peter was unable to walk and had severe developmental issues. Every day at court, he had to be ‘wrestled’ into a suit and preferred sleeping in a corner of his room, rather than using a bed.

Following his escape in 1751, he was issued with a leather collar bearing his name, so as to identify him should he ever wander too far from the homestead.

Peter died at the age of 70 and was buried in the ground of St Mary’s Church with a small, simple marker. While modest in stature, Peter’s memorial stands as a perpetual reminder of the positive change in attitudes to the disabled and those in need.

Steve Marsh’s BMW (1958 – 2009)

Manor Park Cemetery and Crematorium, East London

In terms of grand memorials, we’ve come to expect a certain Victorian group of symbols.

However, in contemporary funeral and burial practises, more personalised memorials are growing in popularity. From football-shaped funeral flowers to a

That said, visitors to East London’s Manor Park Cemetery were a little surprised when a car appeared amongst the headstones.

Steve Marsh was an engineer and dedicated motoring fanatic, who died in his sleep aged only 51. Upon his death, his family commissioned the most intricate and accurate marble BMW, complete with parking ticket and number plate reading ‘STEVE 1’.

Gladys and her Piano (1897-1931)

City of London Cemetery, Manor Park

Gladys Spencer was a popular music and dance teacher, charity worker and Music Hall artist who died at the age of 34.

Teaching at the Classical Academy of Music and Dancing in Manor Park, she worked extensively with child performers as well as being a talented pianist herself.

Little is known of Gladys in life, but the depiction of her sleeping beside her grand piano is a beautiful and unusual memorial to a woman and her passion.

The inscription beside her reads ‘In Loving Memory of Gladys Spencer LLCM. My darling Gladeyes (sic) who passed away 6th April 1931 aged 34 years. The gardener hath plucked a still rarer flower.’

The Cadaver Tombs (1500s)

Winchester Cathedral

More of a bizarre style of

While the rest of Europe has a rich history of macabre tomb effigies, many of Britain’s most striking monuments were lost to the reformation and civil war, leaving few church oddities in situ.

Despite this, several cadaver memorials, or ‘transi’, remain. Cadaver tombs were constructed in the rich history of ‘memento mori’ – meaning a reminder that you will die.

Cadaver monuments take this reminder literally, showing a life-size likeness of the deceased, clothed or draped in appropriate vestments. Beneath this statue, sits the carved decaying corpse of the deceased.

Obviously, these enormous tombs were only the realm of the incredibly high ranking and wealthy.

In Winchester, the two resident cadaver tombs depict Richard Fox and Stephen Gardiner respectively. Both served as Bishop of Winchester in the 16th century and are tucked away in the presbytery, kept behind bars so to avoid the wandering hands of curious tourists.

The Woodplumpton Witch (d. 1705)

St Anne’s, Woodplumpton, Lancashire

Not all graves are elaborate or sentimental affairs; some are cruelly memorialised and born from suspicion.

The woman known as the Woodplumpton Witch was Meg Shelton, a 17th-century maid who gained quite the local reputation for witchcraft and trickery.

It is said she caused illness in cattle, made crops fail, transformed herself into animals and did a whole manner of underhand deeds, earning herself the nickname ‘the Fylde hag’.

Meg died rather brutally, being crushed against a wall by a barrel. Perhaps Meg was a witch? Perhaps she was mentally ill? A public menace? Or perhaps she was simply disliked.

The reasons for witchcraft accusations in the 16th and 17th centuries are multitudinous and tragic. However, with Meg, the legends surrounding her life are only bettered in death.

While Meg is unusually buried in

According to legend, villagers buried her, only for her to claw herself out of her grave on multiple occasions. This led to Meg’s re-burial, head-first, topped with an enormous boulder. Since this attempt, no further sightings of the troublesome witch were reported.

KATE CHERRELL is a PhD candidate at the University of Lincoln specialising in Gothic Literature and Victorian Mediumship. From this, her research has expanded through to 19th death care, celebration and mourning practice. She is also a collector of Victorian death and memorial artefacts and talks widely on these subjects. She holds a keen interest in cemeteries, memorials and supernatural folklore which she explores within her blog www.burialsandbeyond.com. You can also follow her Facebook page.