MARK FRYERS stitches together what is known about lost British horror classic, Castle Sinister 1932

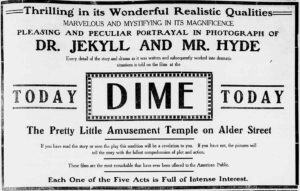

In 1931, Universal Studios in Hollywood established their now iconic gothic cycle of horror films, with the release of Tod Browning’s Dracula starring Bela Lugosi.

This was swiftly followed by James Whale’s Frankenstein, with Boris Karloff as the creature, then Karloff as The Mummy and Claude Rains as The Invisible Man.

These were heavily steeped in the gothic horror of European literature, especially British, as well German Expressionist films, and often featuring British personnel in key roles (Whale, Karloff, Rains etc).

With British Gaumont passing on creating their own version of Frankenstein in 1930, British producers later began clambering to produce home-grown versions of Hollywood horror.

Thus, Karloff was hired to star in The Ghoul (1933), Bela Lugosi for The Mystery of the Marie Celeste (1935) and Claude Rains and Fay Wray for the quasi-horror The Clairvoyant (1935).

Several obstacles stood in their way, however, not least the age-old problem of competing with Hollywood on budgetary terms. Image rights for these classic monsters now also resided with Universal.

This was compounded by censorship issues in Britain which effectively banned the horror genre for a few years before the ‘H’ for horrific was introduced in the late 1930s.

Despite these difficulties, after 1932, several attempts were made by British producers to replicate the success of Hollywood ‘shockers’.

The Aforementioned The Ghoul was heavily indebted to The Mummy, whilst Brian-Desmond Hearst’s The Tell-Tale Heart (1934), reversed the Hollywood trend by adapting the work of American writer Edgar Allan Poe.

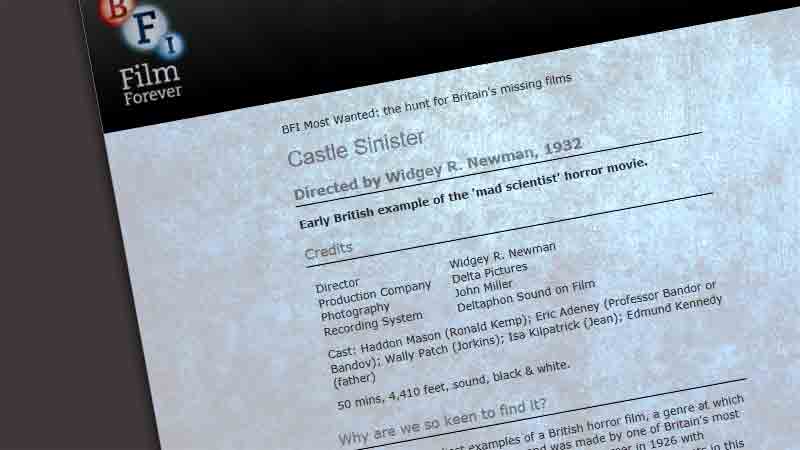

Stepping into the mix was purveyor of cheaply-made British features, Widgey R. Newman, who made two horror features drawing on the ‘mad doctor’ iconography established by many of the Hollywood shockers – Castle Sinister (1932) and The Unholy Quest (1934). Both films remain sadly lost, but research suggests they were incredibly important early examples of British sound horror.

What happened to Castle Sinister?

Castle Sinister clocked in at only 50 minutes (4,410 feet), which was symptomatic of Newman’s austere production methods and those of British ‘Quota Quickies’ (cheap films made to fulfil quota obligations for British product) in general.

The film was trade screened in London, Liverpool and Manchester in April 1932, and was reviewed in trade paper Kinematograph Weekly in the same month.

This review, alongside another synopsis in Bioscope, offer important information as to the look and feel of the lost film, as well as it’s narrative structure. Kine offers the following:

‘Ronald Kemp, visiting a remote castle, is pressed by his host, a professor, to stay the night. In the course of it, Ronald meets Jean, who entreats him to help her father, who is kept under observation by the professor. This intercourse is watched by an ape-like monster, who jealously attacks Ronald. Jean summons the professor to help; instead he threatens to use Jean for his experiments in brain grafting. The monster then attacks and kills the professor. Jean’s father is freed, and she and Ronald join him in leaving Castle Sinister.’

We can see, therefore, that the film follows the ‘mad doctor’ template and iconography established, partly by Universal’s Frankenstein (the castle, laboratory and characters congregating on a stormy night).

The Bioscope review offers further information, such as the film’s action as taking place in Devon. Crucially, it adds that the professor’s experiments are based on the theory that rejuvenation is possible by the transfer of glands. Again, this bears comparison to Frankenstein, in which the Baron is convinced that human rejuvenation is made possible by utilising a colour beyond the normal spectrum.

Whilst not especially complimentary about the film, the Kine review does point to the film’s possible merits. It praises the performances of both Eric Adeney as the professor, who provides a ‘sinister feeling’ and Wally Paul (providing light relief as Jorkins- possibly an Igor-like assistant).

Ape man make provides ‘short thrill’

It mentions that a ‘short thrill’ is created by the make-up of the ape-man. It also suggests that an ‘eerie atmosphere is provided’ by the tactic of filming only portions of rooms and leaving the rest in darkness. This is echoed in Bioscope, which writes that atmosphere is established by ‘a constantly howling wind’ and a smattering of ‘skulls and skeletons’.

The film’s status as a ‘quota quickie’ is evidenced by the fact that the film did not appear to have achieved mass distribution, perhaps best summarised by Kine’s assertion that it may appeal to an ‘uncritical audience’ and best for ‘industrial halls’, a shorthand for working class areas.

This is corroborated in a review in The Era newspaper which describes the film as a ‘mystery-thriller’ that ‘should go down well with the not too-sophisticated audiences’. It screened for a short while in London as well as Kildare and Waterford in the Irish Republic, but little beyond that.

These reviews therefore offer a tantalising glimpse into what is a sad loss for enthusiasts of British horror film.

We can ascertain that the film offered a British variation of the ‘mad-doctor’ trope and that British producers were alert to the appetite of the film-going public for horrific stories, later more successfully exploited by Hammer and other producers.

The film also appears to have influenced the later Boris Karloff film The Man Who Changed His Mind (1936), which also features a mad doctor and human/ape brain transplants.

Another film bearing the name Castle Sinister appeared in 1948, but was set in Scotland and had little to do with the earlier film’s narrative, instead focusing on Nazi espionage.

This further emphasises the fact that the original film now exists only in tantalising fragments- from reviews and synopses of the time, and indeed, in the imagination of the horror fan who imagines what we may be missing.