ELLIOT DAVIES delves into the world of The Lancashire Witches from a secondhand book he bought at an Oxfam

I picked up my copy of The Lancashire Witches in a Manchester Oxfam. Although it appeared in the classics section, I initially supposed it to be a product of the Dennis Wheatley school of 20th century occultsploitation trash.

I bought it anyway, though. Partly because I’ve always been attracted to the idea of dark Sabbaths on Pendle Hill, but also because I’m exactly the sort of person whose questionable interests were ripe for exploitation by Wheatley and his ilk.

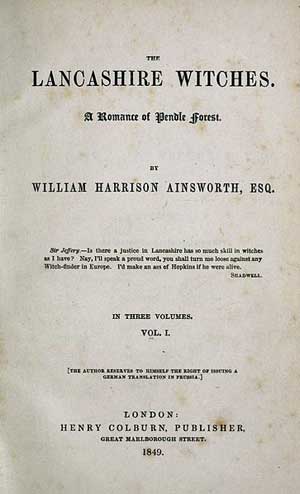

I was surprised to learn that William Harrison Ainsworth was not a contemporary of Wheatley. Rather, he was a contemporary of Dickens and Thackeray. He appears to be remembered by few and read by even fewer.

The Lancashire Witches is the only one of Ainsworth’s 40 novels that has remained in print since it’s initial 1848 publication. Wouldn’t it be wonderful if here we have a forgotten masterpiece from a forgotten genius whose visionary style easily matched – nay, surpassed – that of Dickens?

Sadly, no. I hate to say it, but the reason Ainsworth is arguably all but forgotten might have a lot to do with the fact that he really wasn’t very good at writing.

If you want a harrowing account of the accusations of witchcraft that made life a living hell for the innocent women of Pendle exactly four hundred years ago, look elsewhere. In The Lancashire Witches you’ll find little to love beneath the stodgy mire of purple prose and class-based snobbery.

Really, I’m amazed I managed to persevere with The Lancashire Witches. The first 15 pages or so were really dreadful. Ainsworth enjoyed drowning his readers in overwhelming dumps of information. Not content with overloading his paragraphs with socio-economic explanation, he also has his characters greet each other with long-winded exposition.

Witness this sterling example of naturalistic dialogue:

“Night is approaching,” cried the tall man in the velvet mantle impatiently, “and still the signal comes not. Wherefore this delay? Can Norfolk have accepted our conditions? Impossible! The last messenger from our camp at Scawsby Lees brought word that the duke’s sole terms would be the king’s pardon to the whole insurgent army, provided they at once dispensed, except ten persons, six named, and four unnamed.”

717 pages of that would be bad enough, but it gets worse. That’s just how the nobility speak. Anybody who isn’t rich or good looking is cursed to speak in some downright insulting dialect which comes across as an approximation of no language ever spoken by anybody, ever:

“Ey knoas neawt abowt him, lort abbut, ‘cept that he cum to Pendle a twealmont agoa…boh ey knoas fu weel that t’eawt-cumbling felly robt me ot prottiest lass i’ aw Lonkyshiar – aigh, or i’ aw Englonshiar, for t’ matter o’ that.”

You get entire pages rendered unintelligible by that condescending literary device. Worse still, things are seldom “said” in this book. Rather, they’re cried, observed, pursued, muttered and, at a particular low point, vociferated.

But beneath all these crimes against writing, does their lie a bloody good story just waiting to be unearthed by those with fewer literary neuroses than I?

Very, very nearly. Once things get going, The Lancashire Witches almost draws you in. The opening scenes, in which a curse is cast upon the Demdike name for all eternity, is marvellously gloomy. Also early on comes a brutal and rather upsetting account of a trial by water for a young maiden.

But the more the book progressed, the more I started to feel nauseated. The Pendle “witches” were not, of course, witches. They were innocent and misunderstood women persecuted by a misogynistic patriarchy and a merciless careerist judge.

The Lancashire Witches, though, is not a historical novel. It’s a romance. In this book, witchcraft is a very real force. Therefore, the misogynistic patriarchy, though presented in a less than flattering light, really is portrayed as ultimately acting in the best interests of good Christians everywhere.

It’s also the case that pretty much every woman who turns out to be a witch is suffering from some kind of deformity. And, of course, generally without exception they speak with the aforementioned ludicrous “dialect”.

Frankly, the idea that the wrongfully persecuted might have had it coming is such an offensive idea that maybe the work of Ainsworth is best forgotten after all.

Oh, but don’t feel bad for him. Reportedly, on completing The Lancashire Witches, Ainsworth was paid £1000 and granted full copyright of his work. In today’s money, that’s roughly £78,600.

So whilst he’s perhaps to be denied immortality, it’s probably safe to say that he had a good innings.

If you want to read The Lancashire Witches, it‘s available as a free e-book from Amazon.

I cannot stress this enough, though: I wouldn’t recommend it.

Elliot Davies has a blog called NinetyEightyTwo, where he “reviews each and any film I see that I haven’t seen before”. He also occasionally writes for Found Objects. His previous articles for The Spooky Isles are here.