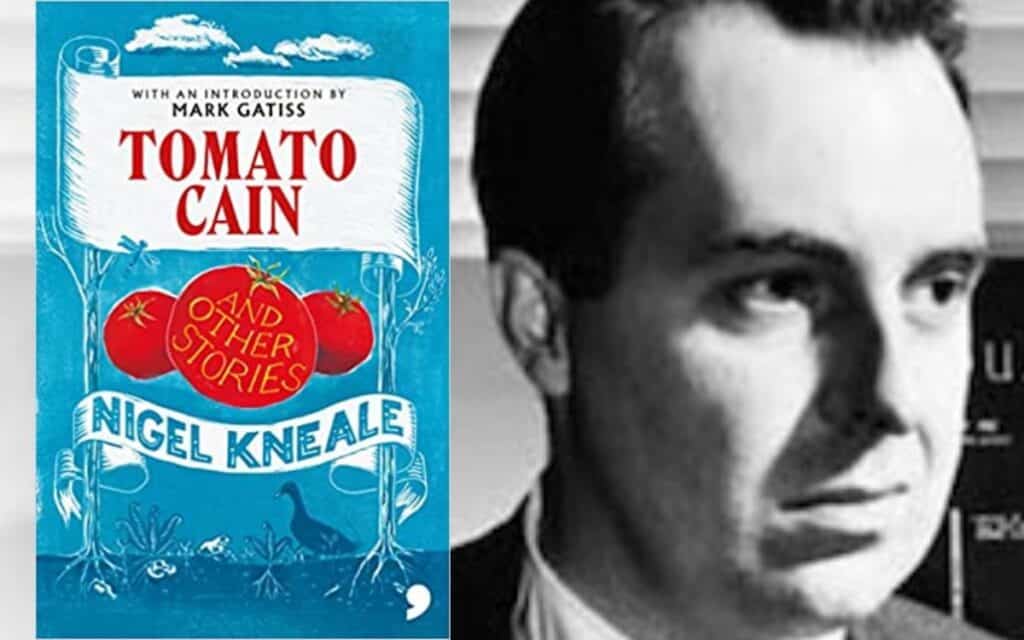

Tomato Cain and Other Stories, published in 1949, is the Nigel Kneale’s only collection of short fiction. JOE HOWSIN takes a look at this recently re-issued work…

Nostalgia is perhaps the most dualistic emotion we commonly experience; it is equal parts comfort and despair, longing and relief. It’s the ghostly invocation of a previous reality that never was or will be again – at least, not in the way we remember. It’s this dreadful yearning that Nigel Kneale captures on film in works like The Stone Tape, and in his one and only work of written fiction – Tomato Cain and Other Stories. Kneale’s settings are wrought with conflicting emotions and unstable realities – the residents of Minuke cling to a world of matter and logic, while the ‘other’ world of inexplicable happenings and unnatural manifestations forces its way to the fore, displacing everything the characters once comfortingly held as fact. However, most stories, like Clog-Dance for a Dead Farce, exist in familiar, ‘mundane’ settings that nevertheless ooze with a certain strangeness – creating a uniquely unsettling atmosphere Elizabeth Bowen calls ‘eminent human queerness at its height’.

Mark Gatiss, in his introduction, references Kneale’s displeasure at being labelled a horror and science fiction writer but goes on to point out the ‘strong thread of genuine ghastliness’ that runs throughout his work. But ‘ghastliness’ is itself a more nuanced term than we credit; while it does fittingly describe the murderous intent – be it human or otherworldly – in Chains, it’s equally applicable to the achingly mundane social awkwardness of The Excursion – and if you’ve ever been stuck making small talk with a particularly boring stranger on a public bus, you’ll understand it’s just as ghastly an experience as discovering a screaming ghost stalking the stairs of your newly-purchased research office.

It’s a testament to the impeccable structure of these stories that these two threads of ghastliness often inhabit the same page – in The Patter of Tiny Feet, for example, we’re left to wonder whether we’d rather face the ghostly footsteps of a mysterious spectre, or the odious pretention of the house’s owner. Either prospect is chilling, but in Kneale’s world, human pettiness and spectral hauntings are directly linked: the former is a direct result of the latter and vice versa. This rings particularly true in tragic tales like Lotus for Jamie, in which the heart-breaking finale isn’t the fault of demonic possession or malevolent poltergeists, but due to the apathy and casual cruelty of ordinary people. This is the most terrifying aspect of Kneale’s human horrors – they’re not even particularly horrific. Rare are occurrences akin to Poe’s murderers or Stoker’s prowling predators, most threats come from simple neglect and pessimism, and more often than not, our protagonists suffer due to their own foibles rather than any outside force.

This uniquely farcical take on the typical horror story is the source of much of Kneale’s dark humour, and while stories like Who – Me, Signor? lean into this comedic edge, there are similarly farcical narratives that go in the opposite tonal direction. Flo, for example, is among the most subtly disturbing short stories I’ve read, not only for its lethal events and terrifying implications, but because the detestable actions of the protagonist are the result of temper, selfishness, and stupidity, rather than any Machiavellian scheming. When sharing a hotel room with Hannibal Lecter, the terror comes from his intimidating intellect quietly plotting your downfall; but while a similar nightmare holiday with one of Kneale’s characters will probably end in a similarly bloody way, it’ll likely be a complete accident. Would it be comforting or sickening to lie dying and bleeding, all while holding back a macabre smile at the sheer absurdity of it all?

An often sickening lack of introspection and self-awareness acts as the dark vein that draws Kneale’s characters to the poison chalice of nostalgia – in his televisual work, Kneale bridges the gap between the past, present and future with depictions of ghostly technology, and while that’s certainly present in certain tales, the majority of Tomato Cain and Other Stories locates the shattering of time in a much more human place. A particularly telling moment in The Excursion comes in the expression of being ‘sort of glad […] we didn’t have to live a long time ago’ (82). True, there are many perks of living in modern Britain: supermarkets, access to medicine, next-day delivery, the list goes on. There’s plenty of reasons to feel grateful for all that we have. But aren’t food banks also being used at record rates? Isn’t the NHS under a tremendous amount of strain from historic underfunding? And isn’t Amazon a global monopoly, dodging tax and underpaying workers? Demonising the past can easily transform into a critique of the not-so-perfect future we’ve created for ourselves.

However, the opposite nostalgic impulse is equally attractive – the ‘good old days’ is a narrative we’re constantly fed by various forms of media from the news to Stranger Things. But in Peg, Kneale highlights the absurdity of romanticising the past with the ghost’s memories of ‘the lovely, cuddly, cosy black-out. And the guns and the searchlights and the balloons’, conveniently ignoring the death and misery just under the surface. It’s no use romanticising the past to escape the horrors of the present – they’re already lying in wait.

Returning to the very beginning, in the eponymous Tomato Cain, Kneale highlights the absurdity of romantic nostalgia on a more personal scale. The core narrative is quintessential Kneale – the hilariously petty Cain’s overreaction to ‘a little heap of scarlet fruit. The new tomatoes of John James Quilleash’ quickly reveals a sinister undertone of xenophobia and a stubborn resistance to anything new: ‘they were not a harvest-fruit to sing hymns for, but foreign things drawn from the earth by hot glass’. Cain’s distrust of the tomatoes is depicted as a thinly veiled cypher for his interpretation of the foreign as somehow intrinsically corrosive to his way of life: ‘the things came from South America, whose immorality was a deep concern to all thinking men. “Love apples” were the tomatoes called’. But, in a kind of self-fulfilling prophecy, Cain’s distrust leads to the destruction of his identity as a respected member of the English upper-class – “Tomato! Tomato Cain!” He knew, with a sudden twitch of agony, that Eli Cain Esquire had ceased to exist at a touch’ – unaware that this transformation is entirely down to his own actions and nothing at all to do with the ‘foreign’, ‘immoral’ tomatoes.

That’s not to say we should ignore the past entirely. It often yields useful answers to our most prescient problems; that’s why, while reading any good book is a pleasure, I’ve always found something special in lesser-known gems from a previous time – which Tomato Cain certainly is. In her original introduction, Elizabeth Bowen praises the short story as existing ‘half-way between tradition and experiment’; we’re privileged, then, not only to experience Kneale’s stories as innovations on a constantly developing form, but also as works whose influence can be seen in subsequent generations right up to our own. Bowen’s introduction highlights the fact that literary innovation is a steadily swinging pendulum, rather than a pyramid built higher brick by brick; plot-laden stories give way to more ephemeral mood pieces, transforming the form into unrecognisable new variations, and then back again – a churning soup of story, theme, and structure that’s far more kaleidoscopic and endlessly unique than a simple straight line. I can’t think of a more appropriate perspective from which to view Kneale’s work: as both a harbinger of the future and an artefact from the past.

However relevant Kneale’s depiction of corrosive nostalgia was in his time, it’s gained even greater significance now – the fact that the fears depicted here are present even in 2022 is perhaps the most terrifying aspect of the collection. Though Kneale is not always on the right side of history – there’s the use of certain words that won’t sit well with modern audiences, as well as a few uncomfortable implications – it can’t be denied that Tomato Cain and Other Stories holds its own as a prescient work of literature and a tour de force for one of the 20th century’s most interesting writers. So, go back and read my first paragraph – remember how good it was? Me neither. The past is rarely as glittering as we remember, but the future? Well, I’ll tell you –

You can buy Nigel Kneale’s Tomato Cain and Other Stories from Amazon.

JOE HOWSIN (he/him) works as a copywriter in Manchester, after completing Manchester Metropolitan’s Masters programme in Gothic literature and film. He’s also written articles on Saint Maud, Ghostland, and A Dark Song for Horrified magazine. His fiction can be found in places like Not Deer, The Walled City Journal, Tether’s End, Lost Futures, and Dark Lake publishing’s The Theme is Revenge Anthology. His twitter handle is @FlayThrowsCats.